Creative Spotlight: In Conversation – Jason Thompson

Sacred Shed Doors: Jason Thompson’s Paradoxical Vision of Art and Object

Liverpool Noise’s Creative Spotlight shines for April on Jason Thompson, a Liverpool native with international acclaim. Thompson’s art, a compelling blend of the sacred and the mundane, manifests as richly layered paintings on found wooden panels.

His training under Roger Ackling at Chelsea College of Art informs his intuitive, process- driven approach, where enamel paints and varnish become tools for a continuous cycle of creation and destruction. Celebrated at the John Moores Painting Prize and enshrined in the Walker Art Gallery’s permanent collection, his work stands as a testament to unplanned complexity. Steve Kinrade of Liverpool Noise sat down with Thompson to delve into his unique creative process, focusing particularly on the intricate details of his 2022 piece, The Sun Split In Two.

“I cultivate intuition because I believe following it might allow you to make contact with something very deep.”

Liverpool Noise: You have described your process as “analogous to evolutionary processes” and heavily reliant on intuition. Could you elaborate on how you cultivate and trust that intuitive voice during the long periods of creation?

Jason Thompson: Whenever I have read about the process of evolution I felt it described very well how my painting process works. The paintings do seem to evolve into an image. There are accumulations of random or accidental changes (the marks I make and the wonky attempts to copy them or mirror them) and they are subject to a selection process in the form of my decisions which determine whether they will thrive or disappear in further generations. When many changes happen over many generations a whole new species can emerge with its own identity. That is like the way my images form. Like evolution it is important to realise that there is no final goal I have that I am striving for, no plan (except to make a solid image that can stand up on its own) all decisions are in the here-and-now, are usually quite small and are all trial-and-error. If they work, they stay, if they don’t work they will die off and be replaced.

You ask how I trust the intuitive voice, I’m not entirely sure I do trust it, not completely anyway. This is why my paintings are built of many layers. To make a mark in an intuitive way is one thing, it might have a romantic, gestural “authenticity” but when I then make a copy of it or make a pattern out of it I feel like this simultaneously consolidates that meaning and yet also kills it, and a new kind of meaning is generated (or the illusion of one). And when I do something on top of that, then again it kind of kills what was there and makes something new out of it.

I cultivate intuition because I believe following it might allow you to make contact with something very deep, and even though I say I might not trust it completely I trust it way more than I would trust making a painting that was based on an idea of what would be a good painting, or making a painting about some political issue in which the painting is reduced to being a prop in an argument. If the painting was entirely conscious and deliberate then there would be nothing for me to discover, so I think the unconscious (or at least not-entirely-conscious) needs to play a big part.

Liverpool Noise: ”Sacred Icon and Old Shed Door”: You mention your paintings exist between these two extremes. What specific qualities of each are you aiming to capture, and how do you reconcile them in your work?

JT: For a very long time I have used panels of found wood and paints that are not considered “proper” professional art paint, i.e. mainly enamel paints (I have stopped using this paint now as it is extremely toxic). The glossy enamel paint is supposed to be used on furniture, window and door frames etc. It has a quality of patina that makes you think of these domestic and familiar things, especially when you use many layers of it and sand it down between layers and bash it about as I do.

You might think a sacred icon and a shed door are opposing extremes but look at the worn texture of, say, an Andrei Rublev icon and you can see something similar to the worn texture of an old piece of furniture in that they suggest the touching of countless hands and that they have been well used and loved for what they are. I want to get a sense of these things in my paintings.

I suppose the difference between the icon and the shed door is the difference between the sacred and the profane but I want my paintings to be both of these at the same time.

Liverpool Noise: The act of copying and repeating marks seems central to your process. How do you maintain a sense of spontaneity and discovery within this repetitive framework?

JT: I try to prevent a painting becoming stale by trying very hard to react to it as though I have never seen it before, forgetting what I was thinking of the day before. This is not always possible though, or very difficult and paintings often reach a dead end. I try to incorporate interruptions in working on any one painting so that I can forget about whatever lingering ways of looking at it might remain. One of the reasons I like to paint on wooden panels is that you can do quite drastic things to it. I often need to “break” the painting and then try to fix it.

Sometimes this is just with paint, like just paint over a huge section of it with some jarring colour. Or redefine a shape by re-painting the negative space around it. Often though, because it is made of wood, I will take a saw to it and cut it into pieces and then reassemble the pieces in another way. Sometimes I will remove sections entirely or add new pieces of wood. Sometimes I might take a plane to it and remove lots of paint but leave areas and use those areas to start something new. Between layers I get stuck into it with a sander as this randomises things a bit and brings out flashes of colours from old layers of paint that had been buried. I have set fire to paintings, but I don’t do that now as its not a good idea in a studio full of flammable paints and sawdust! It works though. It puts a distance between you and the surface of the painting, so you are free to think about it differently.

Liverpool Noise: You have spoken of your paintings “outgrowing” their original supports. Can you describe a specific instance where this organic growth led to an unexpected and significant change in a piece?

JT: This happens so often. If you look at the backs of my paintings you will almost always see that it is made of several bits of wood savagely joined together. This is partly because of what I just said about chopping them up and rearranging them, but it is also because once the painting gets underway I might become convinced that the image needs to stretch out beyond its original confines. They always start with trying to fit into the confines set by the dimensions of the panel, but they almost always want to grow outwards. It happens so often that hardly any paintings end up being made from one single panel. I would say that in order for me to take it seriously every single painting needs to go through a phase of, as you say, “unexpected and significant change”. If it hasn’t then I just don’t seem to be able to trust it as having any depth. I’m just not that interested in paintings that are the completion of one single burst of activity. I will do one burst, then another, then another and what you end up with is a kind of palimpsest. I like to pour lots of time into the thing which is eventually revealed in the single moment of the final image.

Liverpool Noise: You had a close relationship with the famous British Sculptor Roger Ackling. What was the most valuable lesson you learned from him, even if it wasn’t directly about the creative process?

JT: It’s hard to say what was the most valuable lesson. Roger was such a great teacher who helped and inspired me in many ways, we had many long talks but they were not usually about painting (or sculpture, I don’t even think of him as a sculptor really). We always seemed to talk “around” painting somehow. One thing I do remember was to do with appreciating the “thingness” of things. We both made use of found objects in our work and I think he made me realise there was a way of thinking about re-using found things that had more depth than the merely practical (i.e. they’re cheaper) or the superficially ethical (i.e. recycling is better than waste). It was to do with paying close attention to the individual properties of each thing you pick up, what is it’s texture, it’s weight? How would it sit on a wall or shelf? Does it have any marks on it already, marks that I can make something of?

It is about doing work which is not entirely based on yourself and your own ideas but is as much based on things that are not under your control and to work with things. It is about having an amount of openness and flexibility. The piece of wood I might find in a skip is a little piece of the universe whose path has become intertwined with mine. It had a life before I encountered it and it will have one after I have finished messing with it, if you think of it like that then you can feel you are participating in a flow of events the beginnings and ends of which you cannot possibly know, and you and your work are just a small part of something much bigger and unknowable.

There is a big show of Roger’s work about to open in Leeds, I’m really looking forward to seeing it, his works are really beautiful.

“The piece of wood I might find in a skip is a little piece of the universe whose path has become intertwined with mine.”

Liverpool Noise: You have previously emphasized the dual nature of your paintings as both objects and images. How does the physical construction of your works contribute to their conceptual meaning?

JT: I think the physical construction of a piece is entirely where the conceptual underpinning resides. In my thinking, a work’s meaning can only be found in the DNA of what it is made out of and the way in which it is made. Anything else is just attaching a meaning like a sticky label. I will often say my work has no meaning, or that they aren’t “about” anything but what I really mean is that whatever they might mean is completely embodied into what it IS. It is not pointing at anything outside of itself to legitimise itself. It is what it does and it does what it is. At least, that is my hope for them.

The relationship between object and image is also a dynamic one. The painting will begin by taking cues from the nature of the object, so at this point the material object is informing the painting. As the image grows it starts to acquire a life of its own and, as I described above, the image starts to grow past the edges of the panel, so at this point the image then starts to inform the material. But because the image never really stays as it is for very long, there starts a kind of loop where the image and the object take turns in directing what happens. The hope is that eventually this cycle will settle and the image and object become unified in a single image/object which is a painting.

I often feel that more traditional paintings on canvas don’t have the same relationship between image and material that I am interested in as the stretched canvas surface is so familiar that we often don’t even see it and we are only looking at what has been put on top of it. I think painting on canvas is so ubiquitous that it means a large part of what a painting really is, its existence as a made object, gets left unexamined.

Liverpool Noise: You intentionally introduce “interruptions” into your process. Can you give an example of how an unexpected event or chance occurrence significantly altered the direction of a painting?

JT: Over the years I have realised that I like paintings to be an accumulation of many bursts of interrupted activity. The idea of sitting down and finishing a work in one sitting doesn’t really interest me very much. The interruptions are so built in to my whole way of making things that every single painting has included chance occurrences and unexpected events, these are the good bits. If you were to see a photo of a work at the start and then jump to a photo of it at the end you will probably not realise they are the same piece. I think the times I have most enjoyed it is when I have taken bits of one painting and joined them onto another one, like grafting one plant onto the root of another.

Liverpool Noise: You write and draw on the back of your paintings. How do these hidden elements relate to the visible image, and what role does secrecy play in your work?

JT: I don’t do this quite as much as I used to. In the past, especially before I had a proper studio to work in, the work I made was much smaller and I made much fewer works. I used to paint things sat with the painting on my lap and because of the smaller size and lack of room they were much more intimate and I would hold them closely to look at them and I think that this closeness and the fact that I only had room to work on about 3 at a time (now I can have about 40 on the go at any one time) meant that they just seemed to have absolutely everything I was thinking about poured into them and onto them. The painting and drawing would just build up and spread over the sides and around onto the back. After art school no one saw anything I did for about 10 years, so it felt like everything I did was quite secret. I had no idea anyone would ever see these things. I think you do better work if you think no one is ever going to see it.

If I do put things on the back they are usually just thoughts or doodles and so might be clues to things I was thinking about as I was working on the front. I suppose you might also consider the many hidden layers of painting underneath the final layer as being secrets. I don’t get anxiety about painting over months of work on the front because I don’t think of them as being destroyed, I think of them more as being buried, so they are there completely and the final image wouldn’t be what it was without them being there. The viewer can tell there is something underneath but you don’t need to see it for it to be important.

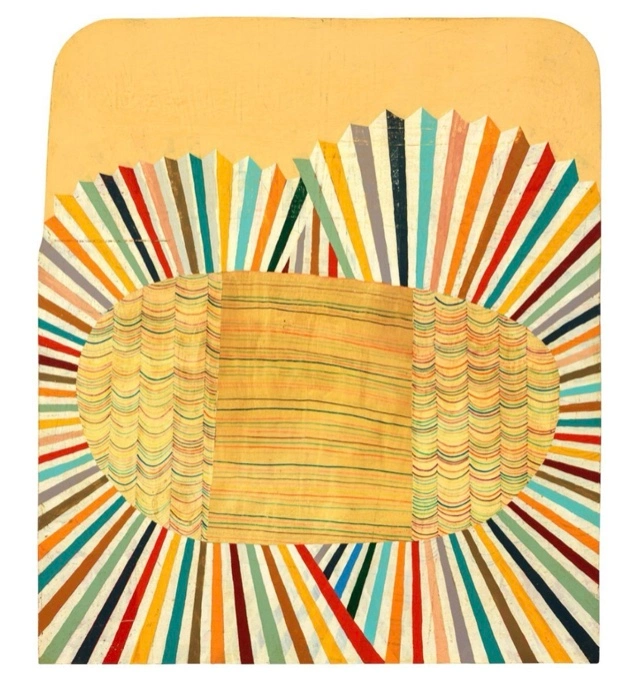

Liverpool Noise: I now want to discuss one of your paintings, namely The Sun Split In Two. Could you give us an insight into how you make creative decisions during the painting process? This is with reference to what cues guide you in varying the colour and thickness of the stripes?

JT: My creative decisions are, in a way, quite straight-forward in that I tend to do whatever occurs to me to do. It is all very unconscious and instinctive (though a tutor at art college once said to me that what we call “instinct” is often just things you think about so much and so often that you aren’t aware you are thinking about them). I will sit and stare at a painting and think about it for a long time but I am not always able to “hear” those thoughts, if you know what I mean. I will wait for something to pop into my mind, I will then try to visualise how it will affect the rest of the painting. I then usually try to forget that thought and visualise something else. And then I try to forget that one and think of another. I do this because my measure of the “best” idea is the one that will not go away. Eventually I give in and paint whatever would not go away. And then I will let it dry and next time I try to look at it all afresh and see what else I can do. Quite often, though, I can look for a very long time and feel like I have made a firm decision and as soon as I get the paint on the brush and approach the painting my hand just goes and does something completely different. The hand “knows” some things better than the mind does somehow.

“The symmetry—especially my wonky symmetry—helps the painting be felt as a (almost) living thing.”

Liverpool Noise: The painting seems to play with symmetry, but with subtle variations. Is this intentional, and if so, what draws you to this “sort of/sort of not symmetrical” approach?

JT: Yes, this asymmetrical symmetry is intentional as what I do not want is a perfect, measured, mathematically precise symmetry. It might be a representation of symmetry rather than symmetry itself. It is the symmetry of natural things, look at our own bodies, nature is analogue and wonky. In my paintings everything is done “by eye” so there will be “mistakes” but I believe this makes everything look more alive and clearly the result of a process of growing. There are lots of symmetrical images in my paintings but its not essential. I am especially fond of it but it grew out of the process of copying and mirroring marks and shapes.

The copying/mirroring feels essential and the symmetry arises naturally out of doing that I think. The structure can form quite easily. Any mark I might initially make can be completely arbitrary or accidental but if you then make a copy of that mark, or echo it in some way, it changes how you see the original, it suddenly has the illusion of a significance or sense of meaning but without signifying or pointing towards anything outside of the painting. Also the symmetry, especially my wonky symmetry, helps the painting be felt as a (almost) living thing. The paintings aren’t representations of a visual space, they are meant to be individual things in themselves that have grown.

Liverpool Noise: The central oval has a distinct texture. What techniques did you use to achieve this effect, and what is the significance of this contrasting texture within the overall composition?

JT: I actually try to not have any intentions when I am painting. This is probably not actually possible but really my only intention, the only thing I try to do is respond to what is in front of my eyes. So the only significance of any part of a painting is that it began as a response to what was already there and it survived because of how it relates to what came after. There are always lots and lots of layers and everything can be buried at any point. That oval section has traces of two separate phases or layers. This is the oldest section of the painting therefore the texture is different, it has been stained and rubbed and sanded more than the other sections so it looks darker and more worn than the area around it. At one time the whole surface was covered in many horizontal lines in many colours. Then most of it was painted out, leaving a kind of tower from top to bottom.

Eventually the space around the “tower” was filled with multi-coloured wave-like marks. Then at some point most of that was painted out leaving a shape resembling a ball split in half, with the halves being pulled apart. From then I think the idea of the sun splitting in half occurred to me and so the radiating lines came in. There were many other stages in this too. I think it looked like a head and shoulders shape at some time. The point is, any intentions I have get lost and swamped in all the layers and what is left visible at the end are fragments of intentions that have all somehow generated each other into existence.

Liverpool Noise: I interpreted the radiating stripes as representing energy and growth. Does this resonate with your intention for the piece? What symbolism or meaning do you associate with these radiating elements?

JT: As I said earlier, at some point the stretched circle shape suggested a ball being pulled apart and for some reason it became a sun splitting in two in my head, and that easily suggests radiating energy. So I painted it and I felt it worked.

View this post on Instagram

Liverpool Noise: How did your time as an invigilator at the Walker Art Gallery influence your working practice, particularly regarding your pocket sketchbooks and the interruptions you experienced?

JT: Doing that job affected my painting in two main ways I think. The first was the little notebooks I made to fit in the pockets of the uniform we had to wear at that time. At that time I had to stand in a room or set of rooms for 5 hours without a break so there was no sitting down. At the same time there were long periods of absolutely nothing happening so I made these notebooks which I had in my pockets. They were about 10 x 7 cm roughly and when no one was around I could get them out and open a page and draw.

So I was drawing standing up, which was very unusual for me. It also really pushed me more and more into thinking of things as palimpsests, or drawings made of many drawings on top of one another. I would open pages randomly and flick through until I saw something I wanted to add to and then scribble on that or blank a bit out with tippex. If someone came in I would have to stop so my whole thing of short interrupted bursts of drawing really took off then. I would have the same notebooks for years so some of them got really full and the pages became really creased and over-worked. I really liked them.

The other way in which the job affected my painting was to do with how much time you spend looking at them and how your opinion of a work can really change over time. I realised that for a lot of the paintings in there, no-one had spent as much time stood in front of them as the attendants did, not since the artist painted them anyway. I found that paintings, even paintings that I initially would like, could just wear off over time, and I often found that the more I could initially find to say about a painting, the quicker it’s appeal would wear off. I came to feel that if a painting is easily describable, i.e. if I can easily translate its “meaning” or the effect it has in words then the painting becomes fixed in your head and you no longer properly experience the painting and instead you just see the words you use to describe it. It becomes buried and obscured by the verbiage supposed to help the viewer understand it.

Similarly, there were paintings that I could find very little to say anything about and if I liked them then I would like them for much longer and would not get tired of looking at them. So all this reinforced very much the attitude I already had that paintings are a non- verbal experience and that paintings that rely on verbal explanations for their effect are always going to be a less profound experience (in my opinion) and if you are going to talk about paintings you should be very careful to leave it open at the end and not suffocate it. It’s always a fear, and I have it right now, as I answer these questions, that every time I talk about my paintings I am painting myself into a corner.

“Each painting has essentially the same DNA, but grows differently depending on the soil it lands in.”

Liverpool Noise: You state you’re essentially making the same painting repeatedly. In what ways do you see each painting as a unique iteration of a continuous exploration, and what core idea are you repeatedly investigating?

JT: I do think I am, in a way, making the same painting again and again, only each time they come out differently. I think of them as leaves from the same tree, or if you imagine a load of seeds from one plant and you scatter them around then each seed, even though it has the same DNA information inside it will grow up slightly differently from the others because of the different circumstances of the soil into which it landed. Each painting I make has essentially the same DNA but they are not exactly the same as each other because, for example, each time the wood I find might have a different shape or texture which puts it on a unique path.

In the studio I will have loads of unfinished paintings hanging on the walls and when I arrive I will look at them and hopefully one calls out to me to do something to it. Some days I will glance at a painting which has hung there untouched for months and all of a sudden I will know exactly what to do to it. Quite often I will realise that I only know this because of something I did to another painting the day before, so the crowd of paintings kind of make each other, they cross-fertilise, they are all related to each other. As a painting comes to completion it gets separated from the others and a new one takes its place, so the fire is constantly being fed.

I think the core idea at the heart of it all is just the urge to be alive and to make things, but I want the things I make and the way in which they are made to somehow be a continuation of what made me and the way in which I was made.

When I said earlier about a painting that “it is what it does and it does what it is”, well I think I’m trying to be like that myself.

Liverpool Noise: What does 2025 have in store for you?

JT: For the last few months I have been making a lot of very small works that are to be in a show in Tokyo in Nidi Gallery. It will be my first ever show in Japan and I’m very excited about it.

I’m also hoping to have another show in London later in the year with the gallery Wilson Stephens and Jones who have been very good to me and shown my work for about the last 7 years.

Liverpool Noise: Jason, we wish you well for the future!

For more about Jason Thompson visit iamjasonthompson.com or follow @i_am_jason_thompson on Instagram.

Jason Thompson was In Conversation with Steve Kinrade.