A Man Vanishes: Review At Liverpool’s Small Cinema

Japanese New Wave filmmaker Shohei Imamura’s 1967 documentary A Man Vanishes had a one off screening as Small Cinema Liverpool this Friday and it remains a treat for any cinephile. Imamura had been an assistant and pupil of the great Japanese director Yasujirō Ozu, working with him on such classics as Tokyo Story. However, Imamura soon began to disagree with Ozu’s vision of Japan and A Man Vanishes is his acidic and biting pronouncement of his view of mid twentieth century Japan.

The documentary is also a meditation of the nature of truth, performance and reality. Imamura blends fact and fiction, actors and real life people in order to playfully thumb his nose at the audience’s expectations on how narrative and reality is usually presented in cinema.

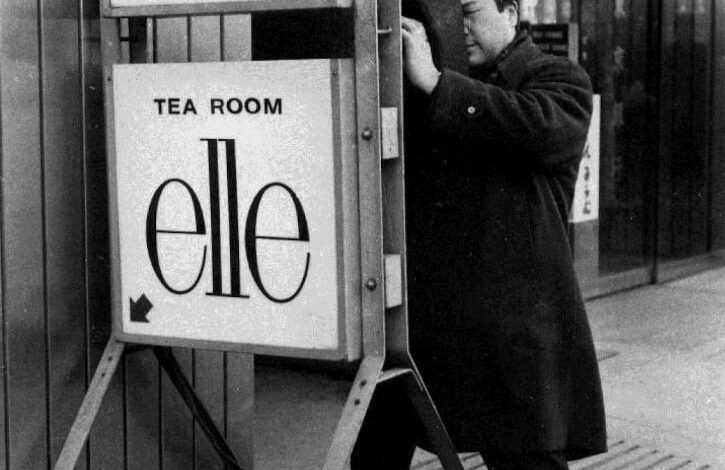

The film centres on the director’s investigation into the real life disappearance of Tadashi Oshima, a plastic salesmen, who had vanished two years previously leaving his fiancé and family behind. Missing persons were epidemic in Post War Japan and Imamura hoped that through the prism of a single case he could investigate something larger in Japanese society.

The documentary then delves into interviewing his employers and family, eventually revealing an embezzlement scandal at work and an affair with his fiancé’s sister. The documentary then takes a surreal turn with the introduction of a fictions investigator (played by an actor and hired by the director) arrives and is set up with the fiancé. The film has been accused of cruelty as it seems to take some pleasure at hounding and making fun of the fiancé as she slowly falls for the fictional investigator. A hidden camera scene in which the finance confessors her love for the investigator is particularly uncomfortable. But, how much of this is real?

Imamura was a master filmmaker, and A Man Vanishes remains a challenging and thoughtful film. But, those wanting the technical flare of his mentor Ozu or the beauty of that other Japanese master Kenji Mizoguchi, will come away disappointed here. The shooting style is deeply straightforward to the point of feeling a little flat when paired with the huge questions the film wants to grapple with. This is also very much a new wave film in the French style – there is a clear influence by French film makers such as Jean Luc Godard. As such it sometimes has the meandering pace associated with some French New Wave films and this is not for everyone.

As a final note, I would like to draw attention to the venue itself. Small Cinema Liverpool is a charity run venue run by volunteers and depends on donations. Nevertheless, it is a first rate cinema experience and offers the people of Liverpool the chance to see films that they might not otherwise have the chance to see, even at more established independent venues such as Liverpool Fact. I would recommend anyone with an interest in cinema or anyone who just fancies something a little different than the usual multiplexes to go and check out Small Cinema Liverpool on Victoria Street.

Faye Mitchell