Creative Spotlight: In Conversation with Jon Barraclough

“To teach is to learn.”

The artistic journey of Jon Barraclough is remarkably diverse – spanning drawing, photography, film, teaching, and research. Born in Bradford, he has lived and worked in numerous cities, including Newcastle, London, New York, Manchester, and now Liverpool and North Yorkshire. He has held significant positions, such as the Director of The Liverpool School of Art, and have been instrumental in initiatives like Drawing Paper UK and the Drawing(Paper)Show.

His current work seems to delve into the narratives held within ourselves and the surrounding world, aiming to reveal a sense of interconnectedness. As part of the Liverpool Noise 2025 Artist Creative Spotlight, we caught up with Jon to discuss his life and work.

“After life in a dirty, male-dominated, noisy factory making gears, art school was like a dream world… Rather than being told what to do, I was being invited to invent and be creative.”

Liverpool Noise: You have had a diverse range of early experiences, from engineering to bass playing. How did these seemingly disparate activities shape your artistic perspective and practice?

Jon Barraclough: My artistic perspective was formed in childhood – my dad was a cartoonist (not professional – it was a party trick that became a hobby). He would sit with me and draw things. I marvelled at his ability to just draw what he wanted – to invent characters and worlds. We’d play a game of squiggles (a kind of drawing conversation) and would take it in turns to draw a meaningless squiggle for the other to turn into something recognisable. Here, decades later I still feel the urge to hover on the borderline between abstraction and representation; to liberate the viewer’s personal visions and understandings.

I left school at 16 with no qualifications and became an apprentice engineer in a factory that made gears. I was told it would be best to get a trade and to become a ‘skilled man’. Skilling-up in this way and working to fine tolerances with metal taught me that sometimes exactness is essential for function. Also that something as seemingly intractable as cast steel can be worked and shaped into very clever things. I also learned that you had to work hard sometimes and to perform repetitive tasks, apparently without fatigue or complaint – and to be the object of everyone’s mean jokes and tricks of course. I felt very out of place.

I never really thought of drawing or making pictures as a potential career until I’d been working for some three years and a friend who I shared house with suggested I try for a place at art school because I ‘could draw’. I was amazed to be offered a place based on a handful of scrappy drawings and some canny talking – but had to go back a year and get some GCE passes at night school before they’d take me. I did my Foundation in Art And Design at Bradford College of Art – in studios which had been previously occupied by the likes of Andy Goldsworthy, Paul Sample and David Hockney.

After life in a dirty, male- dominated, noisy factory making gears, art school was like a dream world. Rather than being told what to do I was being invited to invent and be creative. I experienced a rush of enthusiasm and productivity. I worked all the hours I could and couldn’t grasp why (some) other students weren’t similarly enthralled by the freedom and opportunity to self express. In the 70s it was possible to get a full grant (including college fees) and a materials allowance. I remember saying to my tutors ‘so all I have to do is turn up and make art??’ With a work ethic honed in the factory system, I found it very easy to focus and to push the boat out – to feast on the exploration of this completely alternative kind of ‘work’ was relatively easy and totally exciting. Being productive wouldn’t be enough of course. I also had to find my own themes and voice and also a way of making a living.

Liverpool Noise: Your period in 1980’s New York – amidst tragedy and artistic opportunity – seems pivotal. How did that period influence your understanding of community and artistic resilience?

JB: Working in New York was completely mind bending. I was a photographer’s assistant – running film, printing in the darkroom and helping on shoots and projects. I thought photography was going to be my thing. I enjoyed the processes and the magic of analogue photography – the smoke and mirrors – but also the fine tolerances of working with managed light, celluloid and chemistry. I think the photographic has a strong place in how I draw today – not as in photorealism but as in making light and shade work.

NYC was a very different and scary place to be at the end of the 1970s – but nevertheless overflowing with artists of all kinds and persuasions. The Tribeca warehouse district, just uptown from the World Trade Center, was being offered to artists and entrepreneurs at peppercorn rates in an attempt to revitalise the area. It was my first experience of being in a community of professional artists and it helped shape the future for me.

When I settled back in London in the early 80s I wasn’t looking for a job – instead I gravitated towards a similar scenario in the then run-down Shoreditch. I helped to establish two studios with designers, illustrators and photographers all sharing common space and facilities. (Look at Shoreditch and Hoxton today! Completely transformed). This model of working together with loosely gathered, like-minded people was exactly the right kind of environment for me. I learned so much from working with others and forming collaborative partnerships. There was a steady stream of work and commissions during those years; album covers, posters, books and magazines – it was probably the right time at the right place. The computer had yet to make its way into the industry and most communication was print and paper based. We also worked with primary materials, ink and collage, paint and pastels and cut and paste with scalpels and cow gum.

Liverpool Noise: You worked on graphics for films like Bernardo Bertolucci The Last Emperor. How did the transition from graphic design to film work influence your approach to visual storytelling?

JB: Perhaps my work ethic and openness to opportunity (being up for work that would be challenging and different) helped me move into the film industry for a while. I had some lucky breaks and found myself working for a London based production house called The Recorded Picture Company owned by Jeremy Thomas (his father, Gerald, was responsible for the Carry On films). Influenced by the history of China and Japan, Bertolucci’s epic The Last Emperor was in development and I got involved in the visualisation of a yet-to-be-made film. It hadn’t occurred to me that there was a role for an artist in pre-production. The film was in the throes of being story-boarded and locations were being arranged so reference was available for a kind of prospectus of the film that would entice deals with other organs of the film business; financiers, distributors, actors, crew etc. It occurred to me that narrative can be especially well crafted using drawing. I got to learn how to suggest and imply things visually that were not yet certain or resolved. At some level my dad’s inventive picture making was coming in useful! And around the same time, director Nicolas Roeg (I’d been a fan of his since seeing Performance) was making Insignificance and he was keen to produce of a ‘book of the film’ and I gladly co-authored this with the film critic Neil Norman.

I then began to devote more time to drawing and picture making whilst making money doing record covers and also some theatre work. I was looking for a thread to join up all the experiences I was having and felt frustrated that I had so little time to make work just for myself. I was, however, gathering up ways of thinking and seeing the world through different lenses, if not always my own.

“Drawing has for me two main purposes: gathering up – seeing, observing, collecting – and letting go; a process of harvesting the visual and conceptual stuff and getting it out into the world as drawings.”

Liverpool Noise: You describe your drawing process as ‘gathering up and letting go’ Could you elaborate on how these two approaches manifest in your work?

JB: Drawing has for me two main purposes; gathering up, which I’d describe as seeing, observing, collecting and documenting, – and letting go; a process of harvesting the visual and conceptual stuff and getting it out into the world as drawings. The gathering is at times quite loosely connected to the letting go. It might be a colour or a shape or a gesture that finds its way through to the letting go side of things. Not surprisingly the work I make now can broadly fit into one of these categories – and as the years roll on I’m spending longer on imagining and expressing – perhaps because my eye to hand coordination is less easy to achieve.

Liverpool Noise: You embrace ‘realism, surrealism, and abstraction.’ How do you navigate these different styles, and what role does intuition play in your artistic choices?

JB: I enjoy the juxtaposition of representation and abstraction and this has evolved into a sort of drawing game with myself. How little do I need to say to offer a suggested way of making an image without being too literal and obvious? Sometimes this works – sometimes not. I like the idea that abstract work is creating a world in which something completely unique emerges. Unique in that it doesn’t yet exist in the world. Ultimately the activity of drawing is the lure for me. Since childhood it was always a kind of place that I could go to – a place with few rules or boundaries. A sanctuary. I’m aware that if a few days pass without drawing I get slightly anxious. There’s much said about intuition in the creative process and I think this is something that I struggle with. I often work very freely waiting for an image to work and in some sense intuition is involved.

“I’d like my work to have layers of experience for the viewer – dependent on their desire to see or feel something that resonates with them, but also to trigger sensations that are less exact and more aligned with the subconscious or spiritual.”

Liverpool Noise: You aim to create work that is experienced ‘visually, bodily, emotionally – and perhaps spiritually. How do you intentionally create these layers of engagement in your art?

JB: I’ve now reached the age where I get a state pension and don’t have to do much paid work to get by. Getting rich was thankfully not one of my life missions and giving up teaching and taking on commissions has provided me with the opportunity to get more sustained time drawing and also to find stories and narratives that have been fermenting over the years. I’d like my work to have layers of experience for the viewer – dependent on their desire to see or feel something that resonates with them, but also to trigger sensations that are less exact and more aligned with the subconscious or spiritual. I was raised a Yorkshire Methodist (reluctant – my sister would drag me to church) and have flirted with different understandings of our existential purpose and the ridiculously unique position we have as sentient beings in the universe. I now think the ‘spirit’ is life – all deeply interconnected and interdependent and of course fabulously mysterious in its forms.

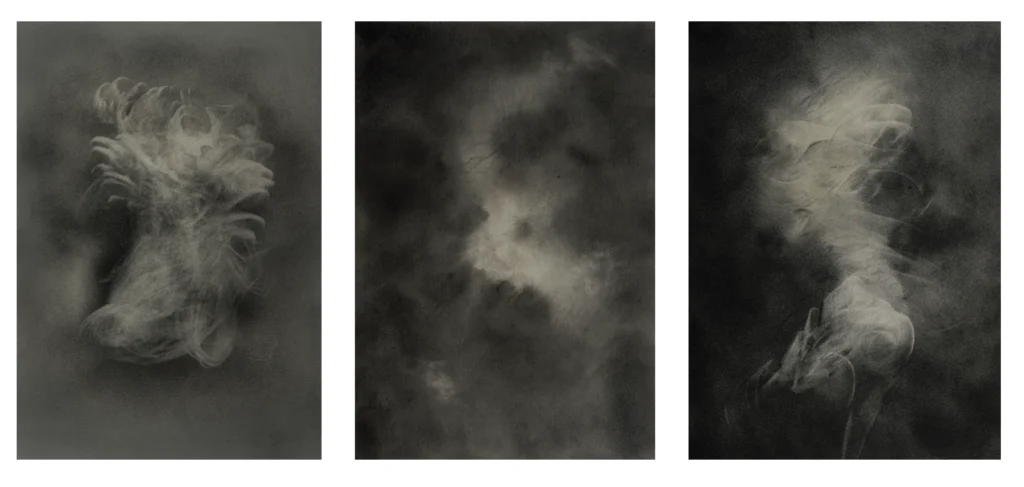

Liverpool Noise: I now want to move to a specific work to discuss, The Silver Fleece, above. The flowing central form, spinning like a vortex, contrasts with a softly blurred background created with a depth-enhancing technique. Tonal variations within the form, achieved through light and shadow, emphasize movement. It’s a really interesting piece.What is the story behind this work?

JB: Firstly it was a real world vision. I spend time walking on the hills of Yorkshire, often solitary, and on occasion something speaks out, initially insignificant, from the landscape. I noticed that birds and animals gather bits of sheep’s fleece for presumably nesting purposes. There before me was a hole in the earth into which something had dragged a twist of fleece. Either I’d disturbed it during its collection or it was left there for future gathering. I was brought up in the wool town of Bradford and the silver fleece was the raw material that brought success and employment to the town during the transition from the agricultural to the industrial revolution. The raw fleece would be washed, spun and dyed in huge factories that many of my family worked in, or adjacent to, for generations. So here is a twist of silver fleece, spinning like a top, disappearing or entering into acreature’s place to be re-used.

It’s interesting that the drawing and the vision happened the other way around. A theme that I like to explore is vortex and the represention of movement using fast whirling marks. I’d been working on this as an abstract motif the night before and then saw the moor top vision of the fleece the following morning. It stopped me in my tracks.I realised then that it was a version of my drawing and so, back in the studio, re-examined it and developed it over the coming days. This was the best of maybe four or five attempts to glue together the abstract with the representational. Here the grassy moorland scrub replaced by a blurry sky-like vista – the fleece/vortex – perhaps heaven-sent.

Liverpool Noise: You’ve had a long and distinguished career in both art and education. What advice would you give to emerging artists navigating the contemporary art world?

JB: I could answer this in an obvious way by saying that if you are single-minded, dedicated and driven then making art will bring rewards. The contemporary art world is, however, a very different place to the one I entered as a young person – as is the workplace generally. It seems you have to be able to prove that you can do something before opportunities come your way. The second half of the 20th Century was an explosion of change and evolution in the visual arts. For a brief period of time there was money around to enable artists and to encourage its practice as a viable industry with rich cultural rewards.

Those times have changed. Today making art has become a more democratic process perhaps. I can now see the evolution of artistic practice and note some of the conversations that are taking place by spending a little time on Instagram or watching some YouTube. It’s possible to make art and to publish it without the cognoscenti having a say in how successful you might become. I hope I’m not being too optimistic to suggest that out of date distinctions like gender, ethnicity, age and social status can represent less of a barrier too. So art proliferates – but in this proliferation, making art a career is maybe more difficult. I’m glad that self publishing and self promotion is available to a very wide range of people and that they find an outlet for their expression. Unfortunately a good amount of it is not surprisingly shallow, often technique-based and maybe fails to move the conversation on.

Liverpool Noise: Looking back over your varied career, which project or period do you feel has had the most significant impact on your artistic development, and why?

JB: If I had to single out a period of my career as having the most significant impact it would be my time spent teaching drawing at The Liverpool School of Art. To work closely with an amazing variety of other novice artists as an enabler and critic helped me to hone my awareness like no other time. For me, to say that to teach is to learn, is an understatement.

Head to jonbarraclough.com or follow @j0ni0la for more info.

Jon Barraclough was in conversation with Steve Kinrade.