Bad Lads: Mike Kenny and Jenny Sealey on Turning Testimony into Theatre

Truth, Trauma and the Power of Telling…

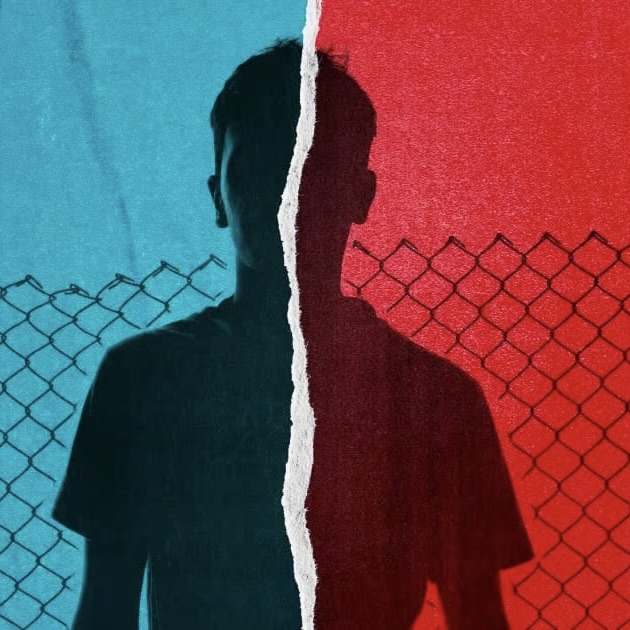

Theatre has the power not just to reflect society but to bear witness—and with Bad Lads, writer Mike Kenny and director Jenny Sealey fulfil that charge with uncommon courage and integrity. Rooted in the testimony of men who endured life inside the Medomsley Youth Detention Centre in County Durham during the 1980s, the production reaches beyond drama into urgent social reckoning.

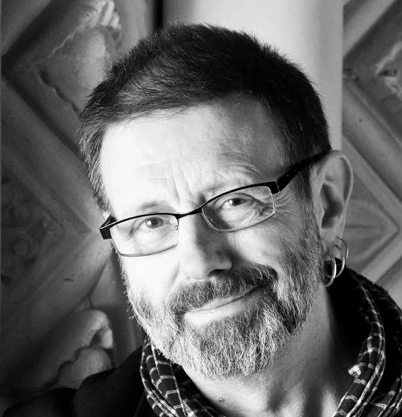

Kenny, best known for his versatility and empathy in writing for young and diverse audiences, here confronts a particularly fraught challenge: translating harrowing lived experience into a theatrical narrative that respects authenticity without resorting to sensationalism. In our conversation, he discusses how he developed a composite character to give voice to many survivors, while preserving the truth of what they endured. His approach signals a profound sense of responsibility—to honour, not exploit, the lives behind the testimonies.

Meanwhile Sealey, artistic director of the pioneering inclusive Graeae Theatre Company, has brought to the staging of Bad Lads an aesthetic of accessibility and human-centred storytelling: the play will integrate BSL, audio description and creative captioning, and the design deliberately avoids theatrical frills in favour of clarity and respect.

Together, Kenny and Sealey have crafted a work that speaks not only to the past—but to the continuing realities of accountability, class, institutional abuse and the possibility of being heard. In the following interview they explore how they balanced the demands of truth-telling and theatrical shape, how they created space for resilience amid trauma, and how a piece of theatre can become a platform for justice.

Steve Kinrade had the opportunity to engage with both Kenny and Sealey, which resulted in a conversation that illuminates the craft behind Bad Lads, the ethical weight of its origins, and the hopeful urgency that drives it…

Given your extensive experience writing for diverse audiences, including young people, what was the biggest challenge in translating the harrowing real-life testimonies of the Medomsley Boys into a cohesive theatrical narrative while maintaining their authentic voices and experiences?

MK: I felt I needed to honour the experiences, not be exploitative, or sensationalist. The method was nearest to the one Jenny and I used when we worked with the experiences of recently disabled military veterans and combined them with the experiences of the disabled of the First World War. Virtually everything in the play was said to us, but it’s not what people would understand as a verbatim piece. We combined the experiences into one character, then split it into two actors, playing the younger and older self.

The play addresses a very specific and painful historical event. Beyond documenting the past, what do you hope Bad Lads will achieve in terms of public understanding, accountability, or even a sense of catharsis for those affected by institutional abuse?

MK: It does look at a very specific historical time, but the demonisation of working class young men, and the circumstances that allowed it to happen, hasn’t gone away. The recent conversation around Adolescence being an example. The state put these guys in an institution and then looked away. For years. The “Short Sharp Shock” policy was created by a generation that had experienced National Service and a class that had been sent to public schools. The stated aim was discipline. The reality was trauma.

How did you approach balancing the profound trauma experienced by the boys with elements that might offer resilience, hope, or even moments of shared humanity within the narrative? Was it important to avoid a purely bleak portrayal?

MK: It’s a good question! Among the men we talked to there was a mixture of opinion. Some said there was nothing positive to be found in the experience. Others, that there was a camaraderie amongst the guys. We saw them give each other a lot of support. My main aim though, was to represent the truth, however bleak. As an act of witness, it has value. It couldn’t be sugar coated in any way. This was done to these young men, in our names. They wanted the truth to be told, so that it never happens again.

The 1980s “Short, Sharp Shock” policy provides a specific socio-political context. How did you ensure this historical background was integrated effectively into the personal stories, illustrating how systemic policies can enable and perpetuate individual suffering?

MK: When we started, I thought we would do a play that would be set inside the detention centre, with a young cast, looking at the short sharp shock, the 6 to 12 weeks they all experienced in Medomsley. As time passed, it revealed itself that there is another play there. There’s also the years that followed, the lifetime of trauma, and the world and authorities that didn’t want to know.

What was your process for working with the survivors of Medomsley? Were they involved in the script development beyond their initial testimonies, and how did their input shape the final version of Bad Lads?

MK: This began with us meeting about 10 men in a room in Newcastle. We had all sorts of ideas, but we jettisoned them and let them talk, for two days. I made no notes, I just listened. They talked, mostly to each other. Which is something very few had been able to do.

Some time later we did the same thing, and also went together to the site of Medomsley itself. Some of the place had been changed, some was the same. We took some flowers, to lay them for the boys who had died.

Our next stage was to get a group of young actors together to explore ways to tell the story, with some of the guys watching and contributing. By this time I had two notebooks full of notes and thoughts on the subject, mostly from the meetings, and partly from stuff gleaned from the internet.

Then I invited two guys to record thorough interviews to track time scales to give me a skeleton on which to build. On this I built the flesh of the play. I took one guy’s experience and wove other experiences into it. Over the course of Operation Seabrook (the police investigation) 2000 had come forward to report physical and sexual abuse. Many had very similar experiences. We created a single character, played by two actors, as young and old. At every stage there was contact and conversation. We couldn’t tell everyone’s story. But we endeavoured to be representative. I didn’t make anything up…

Graeae Theatre Company is renowned for its commitment to accessibility and inclusive theatre-making. How has this ethos informed your directorial approach to Bad Lads, particularly given the play’s sensitive subject matter and its aim to reach a wide audience?

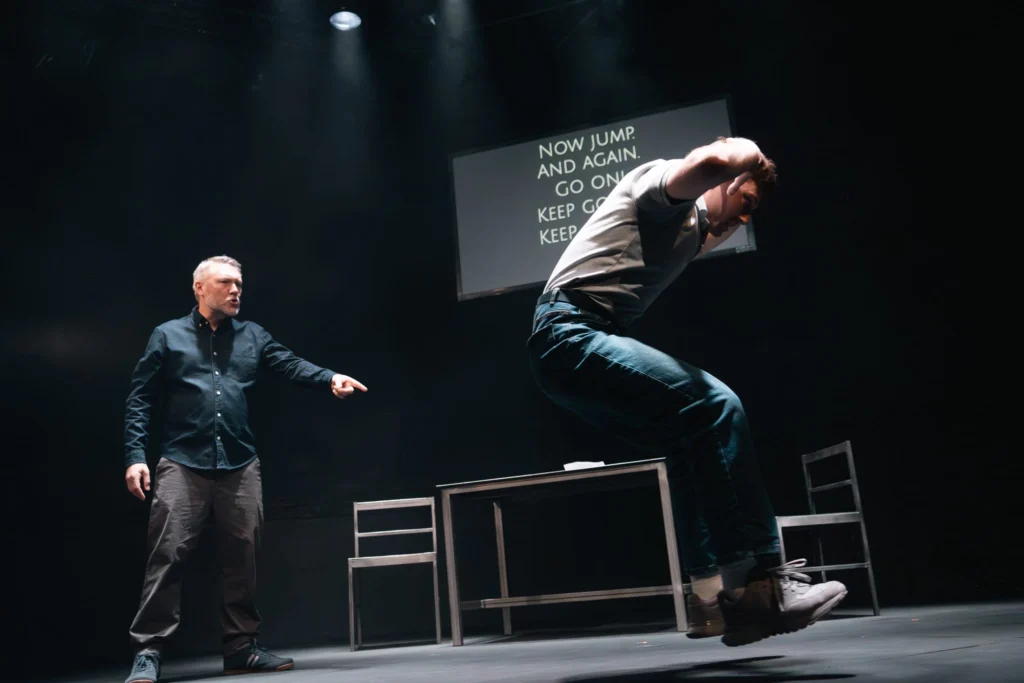

JS: The aesthetic of the Bad Lads production is one of simplicity. It is a no frills or tricksy production as the words of the narrative is our currency. It is captioned and a performance sign language interpreter is carefully integrated, working sensitively with the two actors. The actors share the audio description which is already within Mike’s script because it is a retelling and therefore description is a crucial part of this.

The play is based on real testimonies of profound trauma. What specific directorial choices have you made regarding actor movement, staging, and vocal delivery to respectfully and powerfully convey the experiences of abuse without gratuitously depicting violence on stage?

JS: The power of reliving what happened, means there is no need to ‘act out violence and abuse’. The men do describe and take on the physicality and voice of the various prison officers to create the atmosphere of fear the Medomsley lads lived with when they were there. The struggle the characters have, trying to tell their story is more impactful than any acting out. Graeae’s Self-Rasing had sensitive material, and this too was told straight as there is no point dressing it up with theatrical tricks. I believe simple storytelling is necessary to give the authenticity needed.

How do you plan to create an environment during rehearsals that supports the cast in engaging with such emotionally demanding material, ensuring their wellbeing while drawing out authentic and impactful performances?

JS: In the R&D, it was clear that the two performers believed that it is their job as actors to tell emotionally charged stories. That is why they are actors; it is their job. They are mindful that this is based on true stories, so their commitment to diving into the play is even more profound. They know they can ask for breathing space when the going gets tough and I know that sometimes repeating the same section again and again is not always useful, so I make the decision to move on and revisit the section the next day. I make sure the actors, stage management, interpreter and creative team know they can be open and honest with me and that I have my eye on everything and will keep the space safe to be unsafe.

The best environment for any rehearsal is to make sure access is in place, and work through, problem solving, asking questions, trying different things. The hard work means at the end of the day, we all have a well-earned rest and respite.

Bad Lads aims to make “living history” public. What theatrical techniques or elements (e.g., sound design, projection, set design) are you employing to immerse the audience in the world of Medomsley and ensure the historical context is viscerally felt, rather than just understood?

JS: The retelling of the story happens in a theatre. The set is a table, two chairs and a screen for captions. As we go into the world of Medomsley, the soundscape for the most part underscores the emotional intensity with a few ‘real sounds’ that are essential to the story. The lighting, sometimes stark and bright, also works alongside the atmosphere of the sound to enable us to get into the soul of the character. We see their trauma through light and sound. The captions play with sentences, with words lingering and have moments of being swiped off, like etch-a-sketch. Words can be erased but the memory of what these men went through cannot be.

All these elements enable the audience to see, hear and feel the story and to realise that, by being there as an audience, they are part of the men’s greatest desire – which is to be heard after all!

Graeae Theatre Company presents Bad Lads

5 – 6 November 2025

Liverpool Unity Theatre

Tickets