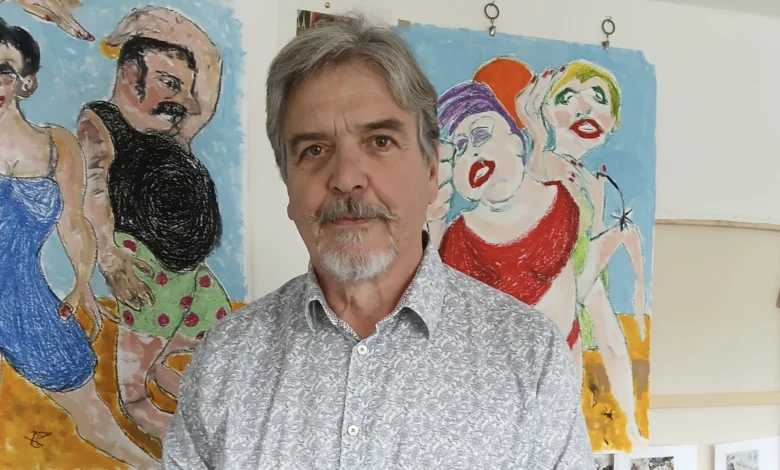

Creative Spotlight: In Conversation with Ted Roberts

From Welsh Roots to Liverpool Shores: Ted Roberts’ Artistic Journey

Welcome to the August edition of Liverpool Noise’s Creative Artist Spotlight, where we shine a light on the incredible talent thriving right here in Merseyside. This month, we’re thrilled to feature Ted Roberts, a Welsh artist whose powerful and evocative work resonates deeply with themes of storytelling, memory, and cultural ritual.

Currently based in our vibrant city region, Ted’s artistic journey is as rich and multifaceted as the pieces he creates, spanning painting, sculpture, and printmaking.

After a varied career that saw him explore diverse paths, Ted made the dedicated dive into art college in Wrexham in 1978, later honing his craft at Cardiff School of Art and the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama. His impressive background as an art director and designer in theatre, television, and film, coupled with extensive experience teaching art and design, has undoubtedly shaped his unique artistic voice.

Now holding an MA in Fine Art, Ted Roberts masterfully weaves personal narratives with broader social and environmental concerns. His current series, I Do Like to Be Beside the Seaside, offers a compelling exploration of the clash between nostalgia, folklore, and ecological breakdown — a timely and vital conversation.

Your work often delves into “storytelling, memory, and cultural ritual.” Could you elaborate on how these elements interweave in your creative process, particularly when moving between different mediums like painting, sculpture, and printmaking?

Ted Roberts: Since childhood, I’ve spent a lot of time living inside my head — what some might dismiss as daydreaming. I think my paintings exist in the space between memory and perception: a shifting ground between the past and whatever “now” I’m inhabiting at the time. I grew up in an environment where storytelling, singing, and poetry weren’t special occasions — they were part of daily life.

Many of my relatives were poets, singers, performers, but also farmers, weavers, blacksmiths, and colliers. Their stories were grounded in the land and their labour. There was no separation between folk culture and everyday life — they were interwoven. Folklore, superstition, ritual, and the rhythms of the landscape have remained deeply rooted in my artistic sensibility.

If I’m nostalgic at all, it’s for a time when such traditions were simply lived — taken for granted and embedded in the countryside I knew as a child.

After a varied career path, including theatre design and teaching, you pursued an MA in Fine Art. How did these diverse experiences inform and shape your artistic voice and current practice?

TR: Working in theatre, TV, and film taught me a lot — especially about responding to a script or brief, and communicating visual ideas clearly and economically. That’s not always how I work now, but it shaped my awareness of narrative and space.

Large-scale productions introduced me to the power of creating environments — immersive spaces that tell a story. During my MA, I created two installation projects: The Beautiful Stream, an ironic response to a polluted watercourse flowing through agricultural land, and We Are All Talking But No One is Listening, a collaborative piece made with students on an alternative curriculum at a Wrexham secondary school.

My time as a teacher gave me the chance to share my enthusiasm for art as a mode of expression. I often found the curriculum restrictive — it didn’t always leave room for real exploration — but for students who were curious, I tried to encourage them to use art as a way of making sense of the world.

The Moon Series emphasizes the moon as a “witness to time, change, and solitude.” What specific memories or nocturnal observations inspired the haunting and introspective quality of these pieces?

TR: The Moon Series began after I moved with my family to a remote spot on the border between Wales and Shropshire — not far from where I’d lived as a child. There were no streetlights, and very little light pollution. At night, especially under a full moon, the quality of the light was unlike anything else — silvery, soft, and strangely commanding. It became the brightest presence in the sky.

I grew up in a house without electricity until I was about nine, so I remember that silver light moving through the sky in a very particular way. It’s both haunting and magical — it leaves an impression.

I think there’s something in all of us that finds the moon enchanting. It holds a kind of quiet power, and it has long figured in painting, poetry, and folk belief. That fascination has stayed with me, and the moon still appears in many of my prints and paintings today — sometimes as a literal object, sometimes as a kind of emotional backdrop.

In Song for My Father, you utilize abstract forms and a muted palette to evoke a “somber, contemplative, or even melancholic mood.” What personal significance does this piece hold for you, given its title?

TR: Song for My Father takes its title from an album by Horace Silver, the American jazz pianist whose work I’ve long admired. I painted it about a year after my dad passed away, so the tone is deliberately sombre and reflective. My father and I were very close, and the landscape depicted in the painting is the one where he spent much of his life.

The moon appears in several guises — glowing in the sky and reflected in the dark mill pond below a bare, leafless tree. The entire palette is cold and muted, speaking to loss and emotional stillness. I wanted to make something that expressed grief without slipping into sentimentality — a quiet acknowledgment of absence, rooted in place and memory.

The Beach Series focuses on “human dramas that unfold along the coast,” often with figures rendered as “ghostlike.” What draws you to the beach as a setting for exploring introspection, ritual, and emotional distance?

TR: Although I grew up in the heart of the Welsh countryside, I’ve spent much of my adult life close to the sea — first in South Wales and more recently in Merseyside. This series began quite informally, through quick sketches of people I saw while walking our dog along the beaches at Southport, Ainsdale, or Formby.

Looking back through old sketchbooks — or scraps of paper, really — I noticed a pattern. My eye was often drawn not to groups, but to individuals who seemed caught in a moment: gazing into the middle distance, or enacting some small, personal drama.

Paintings like Sand Dance and Mask grew out of those moments. The figures became almost like statues, or actors in a Greek chorus — frozen in pose, part of some unspoken narrative. I suppose that’s a nod to my theatre design background.

The quiet dramas of everyday life have always interested me. The Beach Series — like The Street Series — is my attempt to capture those small but meaningful moments of human presence and gesture.

The genesis of I Do Like to Be Beside the Seaside came from a stark realisation about sewage pollution. How do you balance the “nostalgia, folklore, and ecological breakdown” in this series without it becoming purely didactic?

TR: The stark realisation about sewage pollution, as you put it, came about through a moment directly connected to my art practice. I’ve been experimenting with papermaking for over 20 years, often blending recycled materials with natural matter — grasses, dried leaves, that kind of thing — to make my own pulp.

On one occasion, after a series of high tides, I went out to collect vegetation on the marshes. But I found it tangled with sewage and other detritus. At the time, public anger was growing over the state of coastal and inland waterways. That moment — disappointment, sadness, disgust — became the seed for I Do Like to Be Beside the Seaside.

The series began with rapid drawings on large sheets of paper. As I worked, the tone shifted — from bright seaside postcard colours to something darker and more satirical. Though most pieces aren’t captioned, the titles themselves nod to the humour and innuendo of traditional British postcards.

There’s an undercurrent of ecological anxiety, but my aim isn’t to preach. This is just my response to the state of our coastlines. As with much of my work, folklore, history, comedy, and even politics seep into the process — often without planning. The goal is to make the familiar strange, and the strange familiar — as Brecht put it.

I now want to discuss a particular work in some detail…Slumgullion. You explicitly state you are referencing and subverting the classic British seaside postcard. What specific visual tropes or thematic elements from these postcards did you intentionally twist or contradict to achieve your darker vision?

TR: Although Slumgullion is a fictional work drawn from my imagination, the image is rooted in the visual language of vintage seaside postcards — the kind you can still find online. Those old cards often show cheerful, rosy-cheeked children playing happily on sunlit beaches or paddling in sparkling seas.

In contrast, the sea in Slumgullion is a grim, dirty brown sludge, littered with detritus. The beach is strewn with the bones of dead birds and fish. And yet, the two children in the scene play on, seemingly oblivious to their surroundings — lost in the moment, unaware of the filth around them.

The skeletal forms in the foreground could be viewed as the carcass of a dead fish or animal, or perhaps even plastic-like detritus. Were these elements directly observed in real-world settings, and how do they contribute to the environmental message of the piece?

TR: The remains of birds, fish, and crabs are a fairly common sight when I’m walking the dog along certain stretches of beach. These encounters often stay with me and have become the basis for sketches I make back in the studio. In much the same way, I’ve been struck by the presence of plastic waste and discarded fast food packaging — all of it feeding into the visual language of Slumgullion and related works.

The figures’ represented seem to have a naive, almost childlike quality. Was this a deliberate choice in rendering the figures a conscious nod to naive art traditions, or did it evolve organically as you sought to convey a sense of childhood innocence?

TR: Yes, the figures do have a naïve, child-like quality to them — as do others in the Beside the Seaside series. That was partly intentional and partly a result of the way I was working at the time. The images were fresh in my mind, and my ideas were still taking shape, so I needed to move quickly. I often worked across four or five paintings at once to maintain that momentum.

Originally, I imagined the figures being scratched into the sand — like markings made with a toy spade or stick. But the results felt too simplistic and lacked the expressive energy the subject needed. In the end, I opted for a more gestural, painterly approach that better captured the tension in the scene.

Despite the disturbing mood you aim for, the figures, particularly the one on the right, convey joy and engagement. How do you manage to balance this surface joy with the underlying hidden decay to create the satirical tension you describe?

TR: With other works in the series, finding the balance in Slumgullion was challenging — between communicating a meaningful message about coastal pollution and avoiding imagery that tipped too far into farce or ambiguous parody. I wanted the storytelling aspect, along with the reference to the seaside postcard tradition, to remain central.

In the painting, the two children appear completely unaware of the filth around them. They’re smiling, playing happily, caught in their own world. It’s we — the viewers — who are unsettled, even repulsed, by the idea of children playing in such muck and detritus. That tension between innocence and environmental decay is what gives the piece its edge.

The colour palette used is both striking and bold. Could you discuss your colour choices in more detail? For example, how do the vibrant blues, pinks, and yellows contribute to the unsettling atmosphere, rather than merely creating a cheerful one?

TR: It was one of the earlier paintings in the series, and it was originally painted using darker tones throughout. But I quickly realised that the overall effect was too heavy — it lacked the ironic cheerfulness that the scene was meant to suggest.

To shift the tone, I painted over those darker areas with brighter colours. However, the original tones still show through in places, and I think that contributes to the unsettling atmosphere of the final piece. That contrast — between surface brightness and underlying darkness — became a defining feature of the work.

The ambiguous central object can be interpreted as a swirling mass of colours and forms.What was your initial vision for this element, and how important was it for you that its exact nature remain open to interpretation by the viewer?

TR: The swirling mass of colour and form pouring from the bucket at the centre of the painting is the slumgullion of the title. As far as I know, the term originally referred to a kind of stew — made up of leftovers and the barely edible bits of meat that would otherwise be discarded.

It may also have older linguistic roots: slum, an old word for slime, and gullion, an archaic term for cesspool or mud. I first came across the word in the 1990s, when someone suggested it as a name for an art and design co-operative I was invited to join. Its grimy connotations stuck with me, and when I began this painting, the title felt particularly apt — evoking both the murky contents of the bucket and the broader sense of pollution and decay.

Slumgullion contains highly expressive and visible brushwork and impasto technique. Was this choice of brushwork driven by a desire to convey the “messy” nature of the “slumgullion,” or was it more about a broader artistic impulse?

TR: I’d describe myself as an expressionist painter. Physically, that comes through in the surface of the work — many of my paintings reveal the movement of the brush or palette knife, and I often use impasto techniques and textural additives like cornflour or chalk to give the surface more bite.

Beyond the visual message or narrative of the painting, I like the viewer to see the actions involved in making it — to feel the urgency in the mark-making and the speed with which I was trying to get the idea down. Slumgullion wasn’t a slow or contemplative piece. It was painted with energy and immediacy, and I think the surface still reflects that.

You call “Slumgullion” a “satire of nostalgia.” What specific aspects of nostalgia, particularly in relation to idealised childhood memories or seaside experiences, are you most keenly critiquing or challenging in this work? And why name the piece after an American comfort food?

By “satire of nostalgia,” I mean the tendency some people have to reject the realities of the present in favour of an idealised version of the past. While researching old postcards online — the kind I referenced earlier — I was struck by how often they depicted happy children playing on pristine beaches, full of carefree innocence.

But many of those images were created during a time when millions of gallons of sewage and industrial waste had already been seeping into watercourses and the sea for decades. Outbreaks of cholera from contaminated water were still relatively common in late 19th-century England, and many rivers had been rendered lifeless.

So the question becomes: how far have we really come in our relationship with the environment? The tension between romanticised memory and ecological neglect is at the heart of that satire.

The piece suggests influences from Expressionism, prioritising emotionand subjective experience. How do you feel your personal emotions or experiences influenced the creation and execution of this particular painting?

TR: As I’ve mentioned before, I work in an expressionist way — for me, there’s no separation between my personal emotions, lived experiences, and how I create or execute a painting. A work like Slumgullion is an honest attempt to express my emotional response to the environmental breakdown I see happening both locally and nationally.

There are no frills, no superfluous details. If anything, it’s better understood as a momentary impression — like a fleeting thought or a single frame of film. It’s direct, emotional, and deliberately unpolished, because that’s the nature of the subject it’s dealing with.

Given the themes of environmental ruin, lost innocence, and satire, what is the primary emotional or intellectual response you hope viewers will experience when confronting Slumgullion?

TR: I suppose it’s entirely possible that some viewers won’t see beyond the rushed brushstrokes, the unsettling colours, or even the odd title of Slumgullion. And that’s okay. But I’d hope that it might at least spark a sense of curiosity — a question about why the painting was made.

Like much of my work, it’s a personal statement responding to a particular situation that caught my attention. In that sense, it could be interpreted as a kind of diary entry, a note to myself, or even a hurried holiday postcard. It was made by me, for me.

To me, it’s a satirical look at environmental breakdown and lost innocence. Others might see it differently — and that’s fine. My purpose is simply to make the statement, ask the question, and leave space for the viewer to arrive at their own response…

The Welsh Mari Lwyd tradition informs “RisingTide” in your seaside series.How important is your Welsh heritage and folklore in grounding some of your more surreal or symbolic works?

TR: The Mari Lwyd in Rising Tide serves two purposes. On one level, it represents me — a Welsh artist witnessing the early stages of ecological disaster. On another, it stands for the fading of tradition and culture itself. The Mari Lwyd is a potent symbol of Welsh folklore, and its presence in the painting evokes both continuity and loss.

It’s hard to quantify how much of your heritage seeps into your work — it’s not always deliberate. But my Welsh background has definitely surfaced in many pieces over the years, such as the Mabinogion series. I’ve also drawn on broader Celtic and folk traditions.

I’ve long been an avid collector of folklore — from Wales and beyond — and I have no doubt that these stories, characters, and symbols bubble up from the subconscious when I’m working.

”People of the Soil” is deeply rooted in your observations of rural poverty and working-class life in North Wales. How do you approach conveying “rural hardship and quiet endurance” through printmaking techniques like drypoint and linocut?

TR: The characters in People of the Soil are based on people I knew growing up — and on those who can still be found in rural communities across the UK. These aren’t landowners with vast acreages; they’re often tenants making a living from modest plots, supplementing their income with seasonal work. That was certainly true for my family and for many others I knew.

These were also the storytellers, singers, and poets I spoke of earlier — people whose lives were deeply entwined with the land across generations. I’ve tried to reflect the quiet, understated dignity of these individuals in my prints.

Drypoint suits this kind of work — the directness of the mark-making feels appropriate for memory-based images. Every line made is there to stay, and there’s something honest about that. Linocuts, too, have a simplicity and impact that aligns with my process.

Beyond the specific series discussed, what overarching themes or philosophical questions consistently drive your artistic practice?

TR: I don’t want to sound pretentious, but I do think those fleeting moments of drama or magic that intersect with everyday life are still very much at the core of what I do. I find how we interact — with each other, with the landscape — endlessly interesting. I suppose I’m a bit of a sponge in that way.

Sir Antony Gormley once said, “Art is a privilege to make, but only makes sense when it is shared.” That quote comes to mind almost daily. It reminds me that while art-making is often solitary, it’s ultimately a conversation.

In terms of themes, I rarely finish a series and think, That’s it. There’s always more to explore — other directions to take the work. I’m very wary of falling into repetition. If something starts to feel stale or too familiar, I’ll often discard it. I still destroy a fair amount of work if I sense it’s becoming prosaic or losing that spark of imagination. At heart, I suppose I’m a visual storyteller — and there are always stories worth telling.

What are your current artistic goals, and what can we expect to see from you in terms of new projects or explorations in the near future?

TR: One of my main goals is to find the right venue to exhibit I Do Like to Be Beside the Seaside — not just as a series of paintings, but as an immersive installation. I imagine something in the spirit of an end-of-the-pier theatre or old-fashioned arcade. That’s still a little way off — probably a year or more — so I’m not making any serious enquiries just yet. I’ve also been interested in stop-motion animation for quite a while, and I’m planning to incorporate elements of it into the Seaside series — either as part of a projection or as a standalone feature.

I do think there’s room for more hopeful messages about the natural world. My work can sometimes come across as grim, but that’s not really a reflection of who I am — or where I come from. If anything, it’s about staying alert to what’s happening around us and responding with imagination.

Over 50 years ago, an art teacher once told me: “Never stop enquiring or exploring new ideas — the moment you do, you stop learning.” That’s stayed with me ever since. It’s a principle I’ve followed throughout my life as an artist, and I don’t intend to stop now!

Ted Roberts was in conversation with Steve Kinrade.

For more information visit tedrobertsart.com and follow @tedrobertsart on Instagram.