Creative Spotlight: In Conversation with Blaise Drummond

Between Nature and Architecture: Blaise Drummond’s Quiet Pursuit of Balance.

In the latest instalment of the Liverpool Noise 2025 Creative Spotlight series, we turn our attention to Blaise Drummond, a Liverpool-born artist whose work quietly excavates the tensions between the built environment and the natural world.

Raised on the fringes of the city—suburban Heswall, in his case—with marshes, untamed patches of land and the edge of industry always in view, Drummond’s early years planted the seeds of a lifelong dialogue: between structure and wildness, aspiration and decay, memory and place. In this interview he reflects on these formative landscapes; on the influence of modernist architects like Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto; on the uneasy utopian impulse that underpins much of his work; and on the way memory, nostalgia and quiet risk shape his creative practice.

Born in Liverpool in 1967, Drummond’s journey into art has been trans-national as well as interdisciplinary. After an early education that included Philosophy and Classical Art at Edinburgh University he moved to Dublin, graduating with First Class Honours in Fine Art Painting and History of Art from the National College of Art and Design in 1994. He then completed an MA in Fine Art Painting at Chelsea College of Art in 1998.

Over the ensuing decades Blaise Drummond has built a practice across painting, drawing, print, installation and sculpture, producing work that inhabits the liminal space between nature and architecture. His aesthetic is clean, often spare: white or light grounds; architectural forms; trees, nests, buildings; surfaces that draw the viewer in but leave plenty unsaid.

Exhibition and recognition have justifiably followed. Early on, Drummond participated in the John Moores exhibitions at Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery—a crucial landmark in his connection back to his place of birth. He has shown widely across the UK, Ireland and Continental Europe, with solo shows at institutions such as the Kunstmuseen Krefeld, Germany; the Musée de l’Abbaye Sainte-Croix, France; and Galerie Loevenbruck in Paris. Drummond’s work is held in public collections including the Walker Art Gallery, and the Irish Museum of Modern Art.

As Steve Kinrade explored in this interview, Drummond explains how he navigates ideas of balance—between nature and human making, idealism and pragmatism, silence and presence. In discussing works such as The House of the Painter’s Mother (Winter Painting), as well as collaborative and public art commissions, he takes us into the heart of what it means to live creatively in a world where the past whispers ever beside the future…

Having grown up in the suburbs of Liverpool, how did that environment, and the specific tension between the built and natural world, shape your early artistic perspective?

I guess you don’t realise it at the time but obviously the environment you grow up in shapes you. Jonathan Richman has a song that says ‘I want the city, but I want the country too.’ (It’s called City v Country, a title I borrowed for a show of my own years ago.) The suburbs are neither. They are definitely not the city – they’ve fled that. And they are not quite the country either, though they maybe aspire to it. For all that they are a bit disdained culturally. To call something suburban is something of a slur but for me it definitely had its charms. The juxtaposition of a kind of natural world with built settlement produces as you say specific tensions.

I grew up at the bottom of a road in Heswall that ended at the Dee. Though probably polluted from the industry up river those marshes were decidedly non-human spaces, just a 2 minute walk from you but you couldn’t enter them, just stare out over them. There were also a couple of places nearby that I look back on now as kind of remarkable. One was called the Dales and the other the Beacons. They weren’t exactly parks, because as far as I remember they weren’t particularly tended. They seemed to be more like islands or remnants of how the land was before the suburbs engulfed it. That was kind of interesting.

The other thing about the suburbs is that people have the space (and means?) to express themselves in their dwelling. While perhaps not self-consciously how people build and tend the space around their homes reveals all kinds of attitudes about the natural world, community and so on. I guess I was absorbing all these signals at some level growing up amongst that. Things that began to emerge in my work at the point where you begin to express what is personal to you. In my case probably around my 3rd year in art school.

Your work often juxtaposes modernist architecture, particularly the styles of Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto, with natural landscapes. What draws you to these specific architects, and how do their utopian ideals resonate with your own artistic inquiries?

In the 90’s it was more like the buildings I grew up around that appeared in my work – suburban houses or rural Irish architecture and so on. At one point I remember I happened to include an image of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye torn from a magazine in a painting that was riffing off Bocklin’s Island of the Dead. From that I found myself reading more about Le Corbusier and his ideas about the ideal relation between the built and natural worlds. And from there to other modernists with their own particularities, like Aalto reflecting particularly Scandinavian attitudes to the natural world. Their projects often seemed to embody visually the things I was thinking about how we live in the world. They were useful signs to play with in paintings, sucking in with their surfaces all sorts of ideology.

You’ve been known to say your paintings are an “attempt to create some half-remembered vision of balance in the world.” How do you feel your work achieves or explores this idea of balance between nature and humanity?

I suppose at best, hopefully, they poke at an idea (through the materials and their expression as well as in the imagery itself) as if to say to the audience ‘what do we make of this?’ Is it nostalgia? Romantic non-sense, or still some ideal we might aspire to? There’s an American painter called Albert York, who’s work I’m fond of, who said once when asked about his work:

“I think we live in a paradise. This is the Garden of Eden, really it is. It might be the only paradise we ever know, and its just so beautiful, with the trees and everything here and you feel you want to paint it. That’s all I can say.”

As I get older more and more I identify with that sentiment, its optimism and its sadness.

Your practice extends beyond traditional canvas paintings to include “micro installations” and commissions like “A New Path to the Waterfall” at the Royal London Hospital. How does working in three dimensions allow you to explore themes differently than in a two-dimensional format?

Though I seem to be working less and less in 3 dimensions to me it never seemed any different. I always wanted the 2 dimensional works I made to speak across a space to each other to make a conversation, to make effectively a single work out of all the parts. To include 3 dimensional objects in this conversation generally just served to expand the activated space, though they also allowed the play between the language of depiction and the things themselves which can be fun.

Your practice extends beyond traditional canvas paintings to include “micro-installations” and commissions like A New Path to the Waterfall at the Royal London Hospital. How does working in three dimensions allow you to explore themes differently than in a two-dimensional format?

Though I seem to be working less and less in 3 dimensions, to me it never seemed any different. I always wanted the two-dimensional works I made to speak across a space to each other, to make a conversation, to make effectively a single work out of all the parts. To include three-dimensional objects in this conversation generally just served to expand the activated space, though they also allowed the play between the language of depiction and the things themselves, which can be fun.

My research mentions you’ve recently been drawn to the history of Black Mountain College. What aspects of its experimental, interdisciplinary approach and influential alumni, such as Josef Albers, have specifically “seeped” into your current work?

Yeah, I’ve actually been fooling around with Black Mountain stuff on and off over the last 20 years or so. The funny thing is I hadn’t really thought about why until there was a line in a review or text by someone else about a show I did at Galerie Loevenbruck in Paris a few years ago called A History of Hope, which was almost entirely BMC related.

It said something about modernism in a rural context and it hit me in the face like—damn, of course that’s why it appeals: a modernist pastoral. I’m also drawn to the utopian aspect of the project—the idea of a community around a cultural enterprise like that, working together to make the buildings and furniture, and farm and garden to feed themselves. Like all such schemes it ran aground eventually and ended in despair, but I still have a sort of nostalgia for the idea that people had hope and belief in it for a time at least. Something hard to imagine now in ours.

You’ve talked about the importance of being “first time” and not overworking a painting, particularly with the unforgiving chalk ground you now use. What role does risk and the “charge of fear” play in your creative process?

I suppose because I have tended to rely on large areas of clean ground in the paintings (and drawings), regardless of whether it’s chalk or acrylic, it has meant that any marks put down tend to be final, rather than provisional, as in a lot of painting.

There’s a freedom in making a mark that you know can be buried later if it doesn’t work—which is something I don’t usually have. Instead I’ve had to find the freedom in the acceptance of accident and chance. You are trying to control the paint but accept that sometimes it will do its own thing regardless. And experience tells you that it might turn out more interesting than what you had in mind anyway, so that takes away fear, I think.

Painting is a cruel medium in some ways and will reveal hesitation and fear very readily. It is, after all, a frozen record of the brain’s activity via the movements of a body, so anxiety or confidence is plain for all to see.

The Louis Vuitton project, The Arctic, is described as a “unique vision of contemporary travel.” Could you discuss your process for creating the 100 drawings for the book and how you approached capturing the essence of a place through a more curated, distilled lens?

I spent a few weeks staying in Svalbard and then Greenland in 2014—in boats, planes, on foot, and in kayaks—taking photographs. A few days in I realised that as it didn’t get dark at night (it was summertime), I could carry on working, traipsing about, looking at stuff.

At the end of that I had thousands of photographs, and then it was a matter of going through them and thinking which had potential to inform drawings. I ended up with a few sheets of scribbled ideas and then I just had to knuckle down and get on with making the drawings.

The volume (actually 120, I think) was a little intimidating, so I would scan the ideas sheet each day and think: which seems like it might be fun to try now? I kept myself amused by fooling around with different ways of making them—collage, pencil, watercolour, sewing and so on. The resulting drawings, you’d hope, distilled some of my experience up there to convey something of what the place is like for someone who has never been (which is most of us).

I’d like to now ask you some questions about a specific piece — The House of the Painter’s Mother (Winter Painting). This work is currently part of your latest exhibition, a joint show with the artist Robert Sherratt called As The Summer Turns To Rust. Blaise, it’s such an evocative title. Can you tell us about the personal story behind this house and why you chose to paint it?

I know it probably sounds absurdly precise to the point of a cranky poetic, but it’s actually my attempt just to record what it is accurately and distinguish it from other closely related works.

A former student and friend of mine at the art school where I teach in Galway is a painter from Sweden named Cecilia Danell. She lives in Galway but a few times a year returns home to her mother’s house where she gathers research for her own work out walking in the forests there. She’s a pretty prolific Instagrammer and I always see her posts about these visits home.

Some years ago she posted a photo of her mother’s house and something about it just struck me — maybe the colour of it (I like red on green), the setting amongst trees, the children’s storybook quality of it? I don’t know, but I made a painting from it called The House of the Painter’s Mother. I made another one later from one of her summer visits home. It had her mother’s horse in the foreground and was titled The House of the Painter’s Mother (Summer).

It snowed when Cecilia was home this winter and I had the poor woman plagued taking photos for me of the house — texting her things like “more of the tree on the right, closer in,” etc. Those images were the source of this painting. But I’d already done a drawing version of the same, so that is why it says Winter Painting rather than just Winter, to distinguish it from the drawing.

Winter is an important framing here — everything is stripped back to essentials. What drew you to present the house in this season rather than in spring or summer?

As you see above, it’s becoming an ongoing engagement. Naturally, to see it under snow, when I’ve become familiar with it through images of other seasons, looking so different and yet the same, was interesting to me.

There’s something about the fact that it’s a place I’ve never been, yet I have a familiarity with it through these images over the years, seen through the eyes of someone to whom it’s home, that I find kind of intriguing. Perhaps there’s also something of that feeling we tend to have in Ireland and the UK about Scandinavia as some sort of Utopia. Here you often hear in response to political issues people say “In Sweden they…” — like they have all the answers there. Though I realise this is less and less the case currently with the rise of the far right everywhere.

The flatness and sparseness of the snowy ground creates an almost abstract space. Was this a deliberate choice to blur the line between landscape and minimal composition?

I’ve long been in the habit of leaving the white ground of the painting bare. To me it seems natural. People find nothing odd that in drawing the white paper remains the ground for the drawn figure very often. I see a painting as no different to that, though I realise it’s a thing that people frequently remark upon as particular in my work.

It allows me to just include the elements that interest me and ignore those that don’t. Depending on the composition, the unadorned white ground can begin to function as a positive description of snow, which is something that interests me visually in terms of the language of painting. In this case it’s funny that the scene was actually under snow, something that is only made explicit I think in the blue shadow across the ground on the right of the house.

There’s a quiet melancholy in the bare tree, the bird’s nest, and the stump in the foreground. Are these symbolic gestures, or simply part of the house’s environment?

Well, the tree was bare and there was a nest in it, though the tree isn’t actually in that position. I think I made up the stump, partially for compositional reasons and partly as you say for its symbolism.

I’m drawn to a quiet melancholy, but the tree will grow leaves again in the spring and new trees will grow to replace those cut down if we let them. And a nest is a house for a bird — in this case it’s built its house next to the house of the painter’s mother.

You work with oil, distemper, and collage in this painting. What does this particular combination of materials allow you to do that a single medium would not?

Each medium has its particular charms. I like the speed of application of distemper and its matt quality. It dries instantly, recording a very fluid mark, so in this case for example it can describe the conifer very readily. In oil that might be a more fiddly affair, or at least would require waiting a few days for the dark green to dry before pulling across the thinner brighter green. Distemper is also sometimes a little unpredictable, does odd things. Like here the different grey tones in the bare tree trunk just appeared at random, and I like those sorts of surprises in a painting.

I’m more used to the handling of oil in describing the fine details of the building, so I used it there and in the pressed splodge that forms the bush on the left. Thickened with linseed oil paste, oil has a nice quality for that, where its viscosity naturally produces something akin to the veining of branches and leaves.

The collage elements are the nest, the tree stump, and the balcony. Something about using the banality of commercial packaging (in this case a striped brown paper bag from Dunnes Stores) to describe the romantic nature of the nest amuses me in its dissonance — like when you see sometimes man-made elements such as bright plastic bits incorporated by birds into their nest. It’s kind of sad and funny somehow.

Then the stump maybe does the opposite, using wood veneer (which is at once ‘real/natural’ and artificial) to describe wood. It’s sort of stupid but funny, performing a sort of collapse of signifier and signified.

Your work often has a modernist clarity, but with a romantic or nostalgic undertone. Do you see this painting as a kind of negotiation between those two impulses?

Yes! I’m tempted to leave it at that (if it didn’t seem a bit brusque) because that is very well put. We are all made of contradictions and that is one of mine. The negotiation between those impulses probably underpins all the work I make.

There is a pathos in the distance between the ideals of modernism and the quotidian reality that is sort of funny too. The combination of the cynical in the form of a world-weary resignation and the romantic I think appeals to me and reflects a way of being.

How do you approach memory in your practice? Is painting a way of reconstructing the past, or of reinventing it?

I think as you allude to above, there’s a strain of nostalgia in the work that in terms of my specific memories I’d trace to growing up in a genteel suburb with a house full of paintings and books, particularly about the natural world. Books that still espoused a sense of wonder and optimism that has eroded subsequently, with the dawning realisations in works such as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring.

That spirit is probably intermingled with the more universal nostalgia for childhood certainties (for those fortunate enough to have had a stable childhood) — that God was somehow in heaven and all was well with the world. I suppose adulthood can be a sort of expulsion from the garden. It so happens that my generation saw in parallel a wider expulsion with the looming environmental crisis of our own making.

Architecture and landscape often sit at the centre of your work. What is it about the meeting point between human structures and natural forms that interests you?

The structures we make for dwelling tell us a lot about our relationships with the natural world. They are a physical manifestation of our attitudes, thoughts, beliefs, ambitions, and hopes.

In a way a painting like The House of the Painter’s Mother (Winter Painting) is a representation of a proposal. The proposal is made by Cecilia’s mother in living in that structure in that way. I don’t actually know her or anything about her, but to me, looking at images of the house and its immediate environment, which is shaped partly by her and partly by other forces, it makes a statement that this is how to live a good life. This is how the people here think we should dwell in the world.

Another artist might depict a more dystopian urban scene, and I think that too is a form of proposal. In that case probably a negative critique of that which is depicted.

There’s no human figure in the painting, yet it feels inhabited by memory. Was this absence intentional, and what effect do you hope it has on viewers?

There’s no human figure but the whole painting is a depiction of human activity. The problem for me if a figure were present is that I feel it would immediately conjure a narrative around what the figure was doing. As humans we are drawn to looking at other humans and it might suck all the looking into that figure and force a certain reading on the work.

Instead here perhaps there’s the slightly poignant leaning snow shovel outside the porch. In making the painting I felt that that was probably the supercharged point, a small but telling detail — a symbol of work that you might find in a medieval Book of Hours. It is one of the tools by which the landscape is transformed.

In traditional Christian thought a beautiful landscape was one transformed by work. Romantic images of untamed wilderness, that later came to be appreciated, would have appeared horrifying in that context. I suppose a painting like this inserts itself into this space of thought somewhere, questioning: is there a way to live in the world with grace? I would have achieved something if the work evoked thoughts such as these for the viewer.

Finally, what role does silence or stillness play in your work, and do you think The House of the Painter’s Mother (Winter Painting) is ultimately a quiet painting?

I’m probably just growing older, but the world seems ever more frenetic so naturally I am more and more drawn to its opposite. I like work that speaks quietly, that has a quality of stillness. Perhaps a landscape under snow has a world-stopped quality that is akin to the frozen moment of a painting, so there is a doubling down on that feeling in a painting that depicts that very thing.

Many thanks for providing the Liverpool Noise readership with such a deep dive into the creative process and philosophy behind such a stunning work. Now, you’ve mentioned the American painter Fairfield Porter as a recent influence. What about his work, particularly his figurative paintings, has inspired you to reintroduce figures into your own work after consciously avoiding them for so long? You’ve said that it’s important to see paintings in person to understand the “wobbles and the pencil guide marks and brush strokes.” How do you reconcile the fact that most people will only experience your work through digital reproductions?

Ha, yes. And ironically I have never seen a Fairfield Porter work in real life myself. I once went to New York with the plan of heading out to the Parrish Art Museum at the end of Long Island that holds a lot of his work but discovered they were closed for a new install.

I think it is more the way Porter paints than the presence of figures in the work that intrigue me. The best works for me have a sort of cool soulfulness, a poetic reserve that appeals greatly to me. I suppose like Piero della Francesca or Vuillard or in a slightly different way, Caspar David Friedrich.

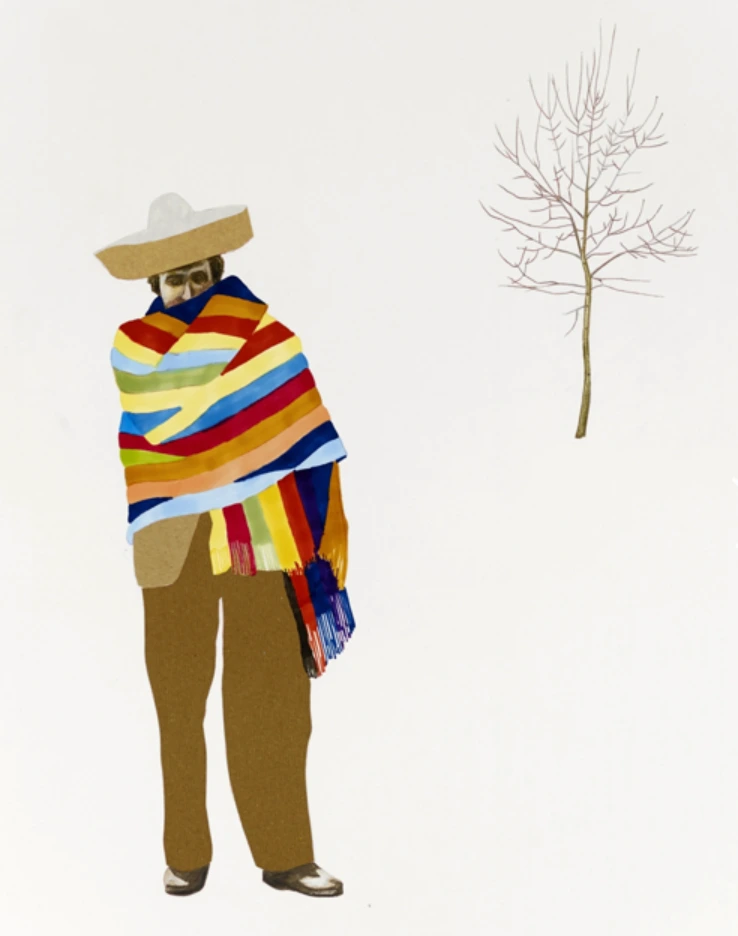

Figures disappeared for a while from my own work when it was more concentrated on landscape, nature, and architecture. They were often present in those works with stand-ins such as chairs and tables. I guess as I began exploring slightly different ways of working it seemed natural that figures might be the subject of some of the works, but I understand after their absence for years (that was sometimes noted in particular) it probably seemed a jump.

As for digital reproduction, yes, it is an odd aspect of our times. When you exhibit work you are aware that the percentage of people encountering it in person is probably a very minute fraction of the people seeing it on screens. All you can do with that I think is try and have as faithful photographs of it as you can, which isn’t easy if you are doing it yourself.

I record the work myself in the studio but despite my best efforts I don’t consider those images to be of a standard I’d want out in the world mostly. It’s a bit frustrating but I am lucky that the work is photographed properly when it arrives in the gallery (Loevenbruck in Paris) by a great photographer, Fabrice Gousset.

The other thing I tend to do is record details which stands in a bit for the way your eye might move around a work, observing different areas.

You often include “little visual jokes” in your paintings. Could you share an example of one of these and explain how humour and playfulness serve as a gateway to more profound concepts in your art?

I suppose an obvious example of that would be where sometimes a painting might include a painted drip alongside ‘real’ drips. Drips and splashes of liquid tend to have a fairly specific scale (the reasons for which could probably be explained by someone more sciencey than me) so sometimes I might paint one at a slightly unlikely scale or copy a real one from elsewhere in the painting and repeat it.

An observant (OK very observant) viewer might notice this and be amused, hopefully, but also at some level reflect on the artificiality of the whole enterprise and become aware of the operation of signs, assumptions and meaning within painting — this white rectangle within which we fool around.

And in the case of a carefully painted drip, perhaps it has wider echoes to our most profound relationships with the world, our ideas of the natural and man-made, control and manipulation of the natural world, and so on.

As an artist with strong ties to Liverpool, with your work held in the Walker Art Gallery, what does it mean for you to have your work recognised and shown in your hometown?

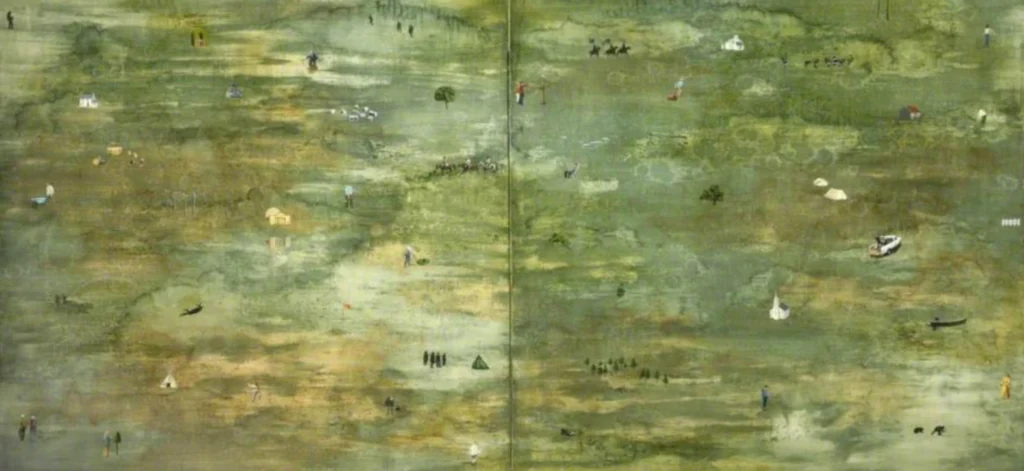

Little Western World, the painting in the Walker collection, probably represents my first step out of the Irish art world. It was in the 20th John Moores (around 1996/7?). The Walker told me they would like to purchase it for their permanent collection, which naturally I was very happy about.

Then I get a call from Charles Saatchi, who at the time was absolutely central to contemporary art in the UK. The gallery was still in this magnificent space in Boundary Road and the Sensation exhibition of his collection was very influential — Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, all that.

I explain on the phone that I’d agreed already to sell the painting to the Walker and there was a bit of “Well, how committed are you to that?” etc. But I felt I’d agreed, so that was that. Subsequently I got the vibe that some people thought that probably wasn’t the best career move, but then, well, there was the fire at the warehouse of his collection, and the other stuff…

So now when I hear that someone has seen the painting on exhibit at the Walker (like my son Sonny saw it there recently and was able to say “Hey, that’s my dad”), I’m really happy that it’s there. Proud, particularly as it’s Liverpool.

Once me and a bunch of friends got suspended from school (St. Anselm’s College in Birkenhead) when we were caught by our chemistry teacher coming back on the ferry after bunking off for the day. The thing that makes me laugh is that we’d spent our stolen time in Liverpool at the Walker and the Natural History Museum next door!

Blaise Drummond’s current joint exhibition with Robert Sherratt — As The Summer Turns To Rust — runs until 11 October 2025 at Galerie Loevenbruck, Paris.