Amartey Golding Talks ‘Silent Knight’: A Powerful Portrait of Prison Life, On Display At FACT

Where Art and Lived Experience Collide…

Some artists paint pictures. Others throw punches. Amartey Golding somehow does both – and neither – crafting work that pulls you in and holds you there, somewhere between discomfort and wonder. Now, this shape-shifting storyteller brings his latest exhibition to FACT Liverpool, and trust us, it’s one for the soul.

Golding’s life reads like a patchwork of place and perspective: born in London in the late ’80s to an Anglo-Scottish mum and Ghanaian dad, raised in a Rastafarian household shaped by a Jamaican stepfather, and moving between Britain and Ghana throughout his youth. That drifting between identities isn’t just part of his backstory – it is the story. His work, spanning film, sculpture, chainmail, and even garments made from human hair, is a raw and unflinching dialogue with heritage, masculinity, and the messy business of belonging.

He started young – selling sketches out of a youth hostel – and dipped into architecture at Central Saint Martins before peeling away from formal study to follow a more intuitive path. These days, Golding’s practice fuses craft and concept with lived experience. One moment he’s hand-weaving chainmail, the next he’s unpacking the myth of Britannia. It’s always personal, and it’s always reaching for truth.

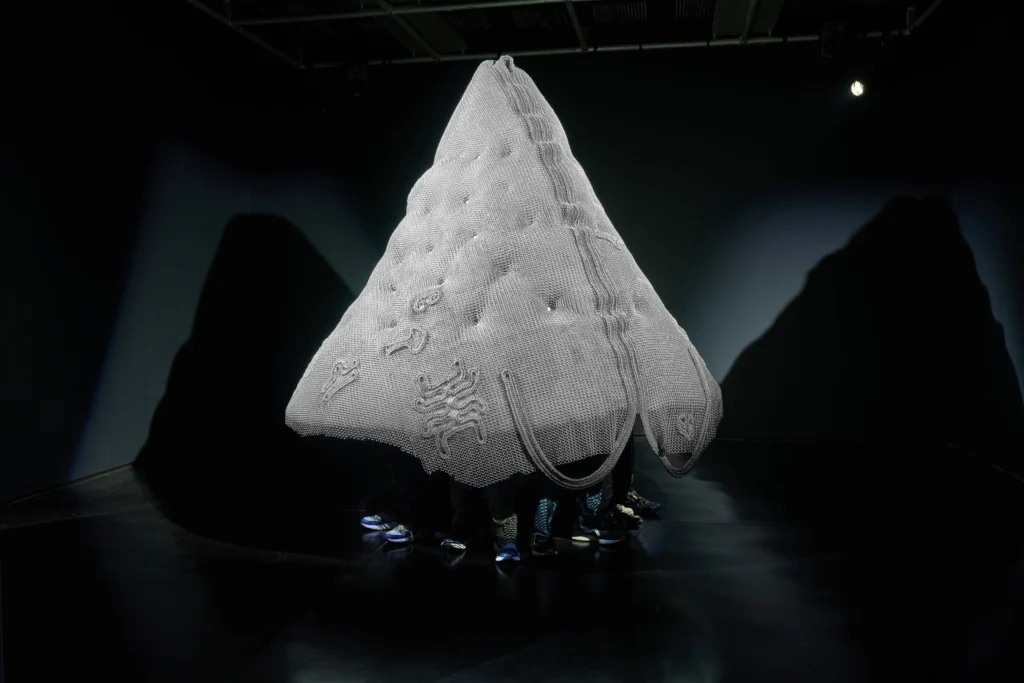

At FACT, Golding unveils Silent Knight, the final work in the Resolution series and the latest in his ongoing Chainmail project. Since 2023, he’s worked with men at HMP Altcourse in Fazakerley to create a monumental suit of armour — over 200 kilos of hand-linked rings, each one shaped by conversation, memory, and time. The result is less a costume and more a monument to survival, protection, and the cost of both. Stitched with their drawings, the suit becomes a lasting record, unignorable.

With a haunting soundscape echoing familiar songs, Silent Knight speaks softly but lands hard. It’s about what it means to be a man in systems that don’t allow softness — and what happens when strength makes room for vulnerability.

Liverpool Noise’s Steve Kinrade got to chat with Amartey and discussed the making of Silent Knight, what he learned from the men inside, and the weight of telling stories that can’t be taken back…

“Being given access to a prison setting — somewhere that’s typically hidden from public view — was a rare and meaningful opportunity.”

What initially drew you to participate in the Resolution project, particularly the opportunity to work within a prison setting like HMP Altcourse?

Amartey Golding: When FACT approached me about the Resolution project, I was immediately interested. The project has been running for about seven years, so it already had a significant legacy, and I was the final artist invited to take part. What really drew me in was the opportunity to connect with a community whose voices are rarely heard — people inside prison. So much of my practice revolves around listening to and engaging with different communities. For example, I have an ongoing series called Chainmail, and another called Anthem, where I travel across the country meeting different groups and having long-form conversations about identity, belonging, and systems.

Being given access to a prison setting — somewhere that’s typically hidden from public view — was a rare and meaningful opportunity. It’s a part of society we all know exists, but most of us have no real understanding of unless we’ve been incarcerated ourselves or have close connections to someone who has. I’ve had family members in prison before and have visited, but only as a guest in the visitor centre. This project allowed me to go beyond that — to walk through the wings, speak with the staff, see the daily operations — and to leave and return, which is something most people don’t get to do. It felt like a once-in-a-lifetime chance to see that world up close.

On a personal level, I’ve always had a strong interest in the justice system — and a lot of questions about it. Like many people from certain communities, I’ve carried a deep distrust of it for a long time. HMP Altcourse is a private prison, a business essentially, and that raised a whole set of ethical questions for me.

“I ended up meeting a much wider range of people — over 50 men across the two years — which gave me a wider perspective on the prison environment and the people inside it.”

Can you describe the process of building trust and collaboration with the incarcerated men at HMP Altcourse during the creation of Silent Knight?

AG: It was an interesting process, and quite different from what I’d initially imagined. When I began, I thought I’d be working with a specific group of men over an extended period. The idea was that I’d return regularly and build up those deeper relationships and conversations. But that plan quickly fell apart. From the very first session, which was supposed to be with a group of veterans, I realised things wouldn’t be that straightforward. The next time I visited, it was a completely different group, and that became the pattern throughout the project.

That was frustrating at first. I was hoping to build trust through consistency, but in reality, I had to start from scratch each time. There were also logistical challenges: the prison was undergoing a management change, and that transition made everything harder. Even just getting inside the prison could be complicated. I’d come all the way from Norwich to Liverpool, often after months of planning, only to find out I couldn’t go in because of some unforeseen circumstance. It made continuity nearly impossible…

Still, there were unexpected positives. I ended up meeting a much wider range of people — over 50 men across the two years — which gave me a wider perspective on the prison environment and the people inside it. Rather than working closely with a few individuals, I had access to a variety of voices and experiences. That diversity added richness to the project.

One of the key things I thought about a lot was the ethics of it all. Many of the men I worked with probably wouldn’t engage with a contemporary art project on the outside. But inside, the opportunity to do something different, to use their minds and hands creatively, seemed to be welcomed. We were making chainmail together — which is surprisingly meditative — and I think a lot of the guys really appreciated the change of pace. No one ever told me they didn’t enjoy it. In fact, many said the opposite.

Because I couldn’t build ongoing relationships with the same people, I had to find ways to ensure their contributions still mattered. Initially, we were just making chainmail in sheets, and I’d take those away and add them to the larger garment. But you couldn’t tell who made what, and that started to feel too anonymous. So I began asking the men to create drawings — symbols, signs, whatever they felt was relevant to the themes — and I’d incorporate those into the final suit of armour. Those symbols are now embedded in the piece. Some came from the officers as well.

In the end, collaboration looked different than I expected. It wasn’t about working with a single group over time, but about engaging with each group I met — quickly, honestly, and without pretence. I tried hard to avoid the kind of patronising tone that can creep into socially engaged art projects. When I was younger, I spent a few years in the YMCA and was often on the receiving end of those kinds of well-meaning but alienating interventions. I didn’t want to replicate that dynamic. I just showed up as myself and treated everyone I met with respect — and I think that helped build trust, even in the short time we had together.

Interestingly, the very first group I worked with actually helped shape the direction of the project. I gave them a choice between two ideas: Chainmail and Who’s Anthem, which is more of a comedy-based, participatory performance about national identity. I thought they’d go for the comedy project, but they really connected with the Chainmail idea, especially after I brought in some samples for them to feel. One of them said something that stayed with me: that chainmail, because of its permanence, couldn’t be altered or taken away, and that mattered to him. That sense of lasting impact resonated, and so Chainmail became the core.

Even though the men from that first group had moved on by the time I returned, their decision shaped the project for those who came after. Each group picked up where the last left off, in a kind of rolling collaboration. It was frustrating at times but also fascinating. In the end, it felt like a collective voice, even if the individuals kept changing.

“The suits I make — they’re heavy, massive, designed for protection. But that same protection weighs you down. It harms you.”

Your Chainmail series often deals with protection and vulnerability. How did working with imprisoned men influence or transform your understanding of these themes?

AG: Yeah, so — protection and vulnerability, violence and care, these have always been central themes in my work. I often say I’m interested in “the grey”: that space where polar opposites become indistinguishable. It comes from my own background — my mum is white English-Scottish, my dad is Black African, and growing up in London I often felt caught in the middle of extremes, of identities.

That sense of contradiction — the idea that we are all more complex, more contradictory than we want to admit — is something I’ve always been drawn to.

Working with the men in HMP Altcourse really deepened that. One of the biggest shifts in perspective for me was around the idea of victimhood. Most of the guys I met — not all, but most — were victims of circumstance. If they’d been born somewhere else, had access to different opportunities, or been given support at a different time in their lives, they likely wouldn’t be inside. That’s not to excuse anything, but it is to understand.

It made me realise: the problem isn’t just the prison system, it’s everything that happens before someone ends up there. The outside world is hostile for a lot of people. Especially if you’re working class, especially if you’re from certain communities. And when survival becomes the main goal, when you’re just trying to keep your head above water, it’s not hard to see how people end up making decisions that land them inside. It’s often not about moral failure, it’s about structural failure.

What really hit me was how many of the men I met had lived versions of the same story. You start seeing patterns. If you’re a bloke from certain backgrounds, with certain boxes ticked — maybe broken home, poverty, poor mental health support, limited education — the outcomes become disturbingly predictable. Crime. Prison. Dead-end jobs. Or sometimes the military — that came up a lot too. These are often the only options made visible.

And what’s heartbreaking is the cycle that happens: many of these men have been victims, but now they’re in prison because they’ve created victims of their own. That cycle — of pain handed down — is something I’ve become deeply interested in.

All of that played directly into my understanding of Chainmail. There’s a beautiful and painful metaphor in there. The suits I make — they’re heavy, massive, designed for protection. But that same protection weighs you down. It harms you. It restricts your movement, your freedom. And for so many of the men I met, that’s exactly how life felt. The very things they relied on to survive, the things that were supposed to protect them, were also destroying them. And I think a lot of the men I met recognised themselves in that contradiction. In the weight of that chain.

So yeah, my time in the prison transformed my understanding of these themes. It made everything sharper, more grounded. It turned abstract ideas into something deeply real — and painfully human.

“So much of what we call ‘justice’ is really just a continuation of injustice.”

What was the emotional or psychological impact of hearing the stories shared by the men as you wove the chainmail rings together?

AG: Frustration. That’s the word that comes to mind first. A deep frustration, not just with individual stories, but with how avoidable so many of these situations felt.

There are these recurring themes that come up again and again in their stories: the backgrounds, the lack of support, the absence of healthy influences, the limited opportunities. You hear it over and over — men whose parents were in prison, and now they’re in prison, missing their own children. The same cycle playing out across generations. That really got to me.

What’s even more heartbreaking is the sense of loss, not just of freedom, but of what could have been. You meet these men and think: You could have been amazing.

So it was emotional — definitely. Especially the moments where I realised: I’m not far off from what they are feeling. As an artist, I’ve felt the same pressure; working myself to the bone and still struggling to get by. It’s not a huge leap from that to making a bad decision in a desperate moment. And the difference between me and some of those men? Honestly, it could’ve been one slip…

So emotionally, it was heavy. Psychologically, it made me feel like so much of what we call “justice” is really just a continuation of injustice. But at the same time, the connection, the fact that these men let me in, shared their stories, trusted me enough to be vulnerable, that was something I’ll never forget. It was a gift.

“Ultimately, I wanted to create a space that’s as much about contemplation as it is about confrontation.”

How do you see Silent Knight functioning within the gallery space, compared to the prison environment it emerged from?

AG: It’s important to start by saying that Silent Knight was first shown inside the prison — specifically in the visiting centre — for two weeks. The men who helped shape this piece had to be the first audience.

In the prison context, the symbolism of a suit of armour is immediately understood. You’re in a space where people are constantly under threat — emotionally, physically, psychologically.

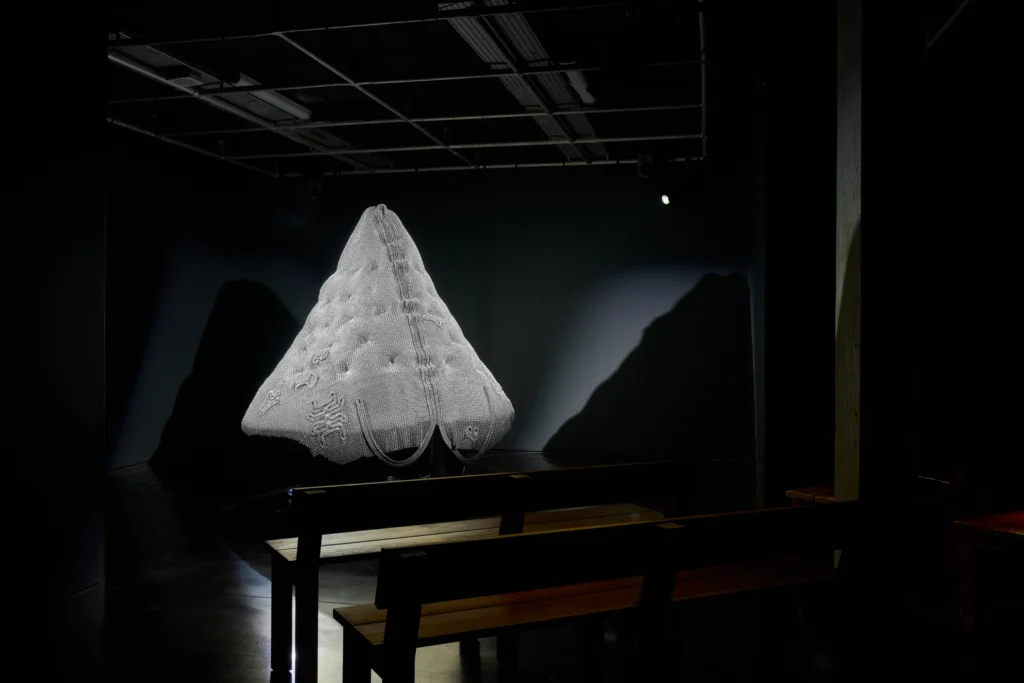

But in a gallery, the suit takes on a different kind of weight — one that’s more layered and, in some ways, more surprising. Because galleries can still be deeply alienating spaces.

So for me, placing the armour in that space highlights another form of protection — the armour we wear to enter these environments that don’t always feel like they’re made for us.

I set up a row of pews facing the suit — seating that could feel like a chapel or a courtroom. That layout was intentional. I wanted to create an environment that invited reflection, redemption and judgement simultaneously.

Ultimately, I wanted to create a space that’s as much about contemplation as it is about confrontation, where people can sit, reflect, and ask themselves: What does protection really look like? Who gets to feel safe in these spaces — and who doesn’t?

Much of the Resolution project focuses on visibility and representation. How do you hope the public responds to seeing the work created in collaboration with incarcerated individuals?

AG: The main thing I hope for is contemplation. I want people to take their time with the work — because time is at the heart of everything this project represents.

I’ve designed the space to encourage that — with seating, with atmosphere, with music — to invite reflection on the bigger questions around justice, representation, and care.

So my ideal response from the public would be for them to slow down and sit with it. Really sit. Touch it. Squeeze it. Feel the weight of it.

Time is also what’s taken from incarcerated individuals, literally, in terms of years, but also in the broader sense of their stories being ignored or erased.

And beyond that, who knows? Once you release a piece of work into the world, it lives its own life. But first and foremost, I hope people spend time.

How did working on Resolution alongside criminologists and justice system experts, like Dr. Emma Murray, impact your perspective as an artist?

AG: It was an incredible opportunity — both as an artist and as a human being.

As an artist, I’m driven by curiosity, and this project gave me access to a whole new field of insight. Working with someone like Dr. Emma Murray… has been invaluable.

This collaboration has helped me approach the work with a more layered understanding of justice, systems, and power.

It’s added depth, not just to Resolution, but to how I think about making art in general — who it’s for, what it can do, and how it can participate in bigger conversations.

Looking forward, has this experience changed how you approach your work or the kinds of communities you hope to collaborate with in the future?

AG: It hasn’t really changed how I approach the work creatively but it’s completely changed what I value.

Spending time with these men… made me look at my own life and ask some hard questions.

Maybe presence—being there, being well, being whole—is the real legacy.

So yeah, this project came at a pivotal time. I wasn’t a dad when it started. Now I am. And it’s made me realise the most radical thing I can do going forward might be to simply show up for the people I love.

I still believe in the power of art — deeply. But now I want to create from a place of balance, from love rather than survival.

Amartey Golding’s Silent Knight exhibition is on display at FACT Liverpool until 10 August 2025. For more information visit fact.co.uk/event/amartey-golding.

For more information about Amartey Golding visit amarteygolding.com.

Amartey Golding was in conversation with Steve Kinrade.