Creative Spotlight: In Conversation with Naive John

From pixels to paint — Naive John builds images that resist meaning and reward patience.

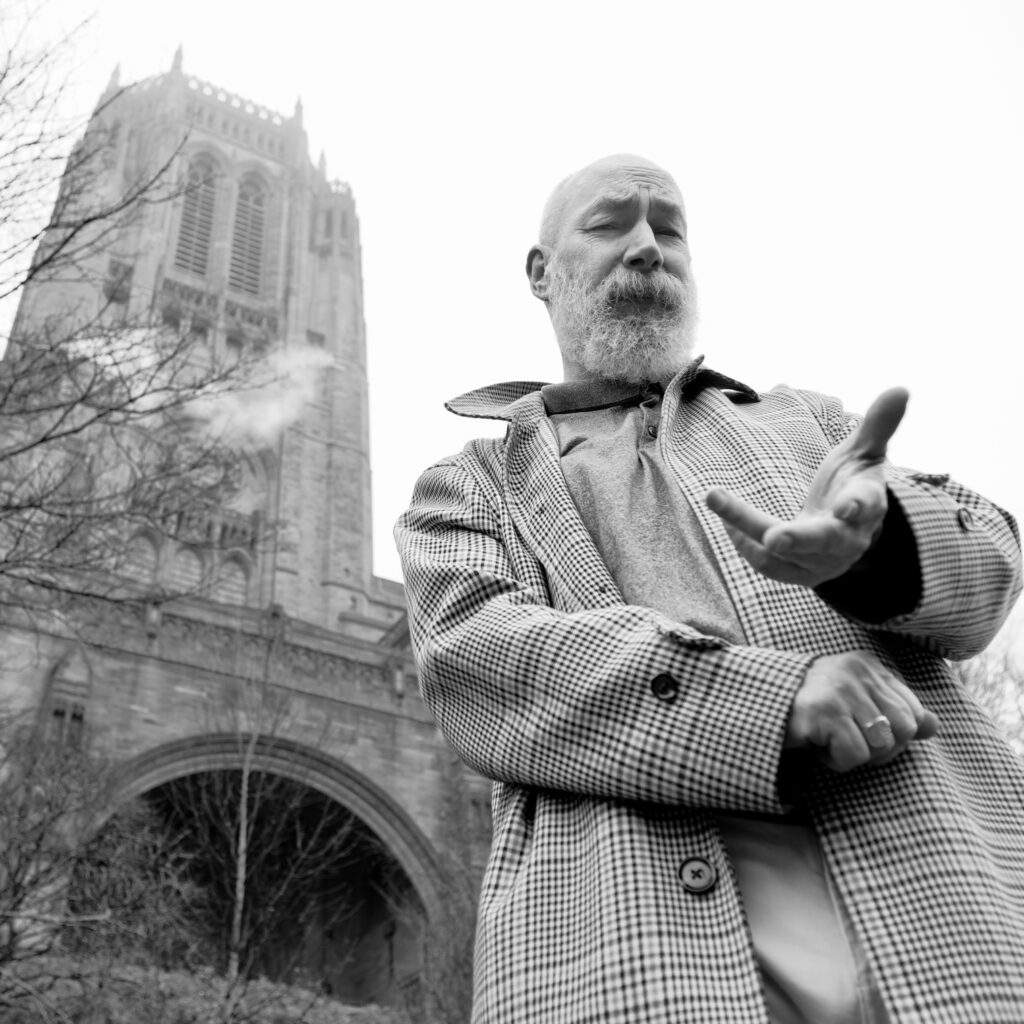

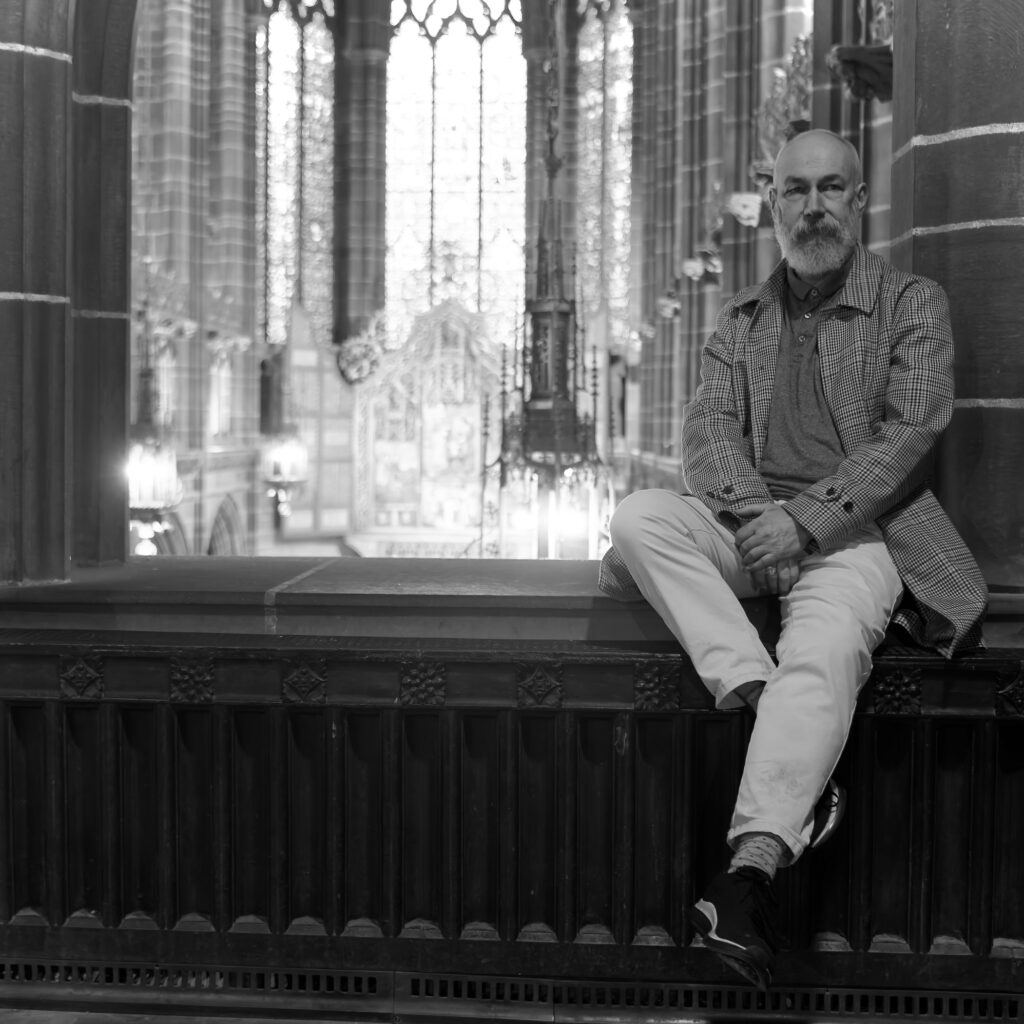

On the edge of Liverpool’s Toxteth district, amid terraced streets and the low hum of passing traffic, there’s a studio that feels less like an artist’s room and more like a laboratory. The light is subdued. Brushes are laid out with care. A monitor glows quietly in the corner. At the centre of it all stands Naive John — painter, digital tinkerer, and craftsman of the uncanny.

He’s been described as a surrealist, an absurdist, a pop folklorist. But for me, none of those labels quite hold. His work occupies a stranger territory, where myth and cartoon, humour and melancholy, digital precision and human fallibility coexist on the same uneasy plane. His paintings feel carefully engineered and emotionally unstable at the same time — seductive surfaces hiding darker undertones.

Born Ian Wylie in 1962, Naive John grew up in Scotland, encountering art not through galleries or formal education but through comics, television and toys. Drawing came early. Painting came before permission. Art school followed briefly, but the experience proved alienating — too rigid, too prescriptive. He left and learned the hard way: through repetition, failure, obsession. That self-taught discipline still defines his working life.

The name Naive John emerged in the early 2000s, but its roots go deeper. It wasn’t a branding exercise so much as a personal rupture — a way of stepping away from an earlier self and starting again. “To make art one must produce something from nothing,” he says. “Making art as Naive John is like that — it’s looking at the world through a magikal lens.” The name marked a shift: from survival to production, from paralysis to compulsion.

Around that time, he became associated with Stuckism, exhibiting at the Walker Art Gallery during the Liverpool Biennial in the early 2000’s. This is where I first encountered his work. In hindsight, he sees that period pragmatically. “It was a useful stepping stone,” he reflects. “I learned a lot about egos and pecking orders. It had no aesthetic impact on my work.” What endured wasn’t the manifesto but the conviction that painting still matters — that the handmade image retains its charge in a distracted, dematerialised world.

Liverpool became his creative anchor after a turbulent period in Glasgow. Drawn by affordability and a sense of openness, he found a city whose contradictions mirrored his own sensibility. Earlier works folded in recognisable fragments of place — Sefton Park, Toxteth pavements, urban edges bleeding into pastoral calm. More recent paintings have stripped that back, edging away from autobiography toward something less anchored, more universal.

What truly distinguishes Naive John’s practice is process. His paintings often begin digitally: ideas that surface while travelling or daydreaming are researched obsessively online, refined, rebuilt. From there, he constructs digital sculptures — posing, lighting and texturing them with meticulous care. These models are then rendered into reference material, translated painstakingly into paint.

He likens this to Renaissance practice, and the comparison holds. Like Titian’s wax figures posed in candlelight, these digital forms are tools — not shortcuts but extensions of an older discipline. The finished paintings are built slowly, indirectly, through successive semi-transparent layers. Acrylics, airbrush and brushwork combine in a method closer to oil glazing than contemporary figurative painting. Edges are softened or sharpened with classical sensitivity. Texture is rationed. Light does most of the work.

“I don’t pre-mix colours in the usual way,” he explains. “All the tonal nuances you see are optical effects caused by layering.” It’s a quiet kind of virtuosity — invisible in reproduction, revealed only through sustained looking. Some works take months. Others stretch to a year. The labour is intense, often anxiety-ridden, but never theatrical. Painting, for him, isn’t ease. It’s necessity.

Visually, the work is immediately recognisable. Cartoonish figures — wide-eyed, rubber limbed — inhabit luminous, unsettling spaces. Beauty brushes up against decay. Humour sharpens into something darker. Flies orbit serene faces. DNA helices intrude on parks and interiors. These are images that feel playful until they don’t — trickster figures for an anxious age.

Cartoons, he admits, were his first visual language. Growing up in a traditional working class environment, they were the culture available to him. “Television and comics were my visual stimuli,” he says. “As for darkness — that’s just life experience. It can’t be all light. We need the shadow too.” That tension — between innocence and unease — sits at the heart of the work.

Despite international exhibitions, including a Los Angeles showing in 2022 that framed his paintings as absurdism for the digital age, Naive John remains rooted in Liverpool. The city’s humour, resilience and refusal to polish itself are echoed throughout his practice. There’s a distinctly northern deadpan at work — laughter that carries weight.

What makes his work so compelling is its accessibility without compromise. You don’t need theory to engage with it. You can be amused, unsettled, drawn in by surface and craft. Meaning isn’t handed over; it’s resisted. As he’s said elsewhere, interpretation — even his own — isn’t the point. The image carries its own authority.

His latest work – The Brilliant Fool – is a limited edition print, and is classic Naive John. As is customary for this series, I asked him some questions about the work, hoping to get a deeper understanding of his process, and was not disappointed…

The figure in The Brilliant Fool seems suspended between comedy and catastrophe. What was the initial idea or emotional impulse that set this piece in motion?

I think it was probably my response to the Universe and my place in it at that time. My way of acknowledging the absurdity of existence and the resilience that’s required to navigate the game of life.

The title suggests a tension between intelligence and self-delusion. How do you see “brilliance” and “foolishness” interacting in this character?

While outwardly ridiculous, “the Fool” can also possess a kind of hidden subversive wisdom. Consider, for example, the court jester who uses humour and apparent silliness to speak truth to power.

Having no real understanding of boundaries – be they personal or intellectual – “the Fool” is free to explore without the usual societal constraints potentially revealing deeper wisdoms and truths. They are the lie that tells the truth.

Is this figure an archetype, a self-portrait in disguise, or a comment on a broader social or cultural condition?

Well, I think the cliché that everything an artist makes is a self-portrait is true, so there’s some truth to that idea but really, it’s just the most current variant on a theme I’ve been developing for years now. From Jokers on playing cards to Fools on the Tarot. Their symbolic meaning alters according to the context they appear in.

One issue, as I see it, is that in giving a definitive answer to this type of question – which is one enquiring about any specific meaning – I would surely, as the work’s author, remove any ambiguities and mysteries for the viewer to participate in. And it’s all about mystery. I will say this though; my intention is to create codified devotional objects. A lofty ambition to be sure!

The character’s body is impossibly elastic while the face remains oddly serene. What does that contrast represent for you?

The beguiling appearance of Dualism; Ying and Yang, this and that, you and me, subject and object, observer and observed.

How intentional was the decision to keep the facial expression almost blissful despite the physical contortion?

Oh, the one thing I can guarantee is that everything in my paintings is intentional. The only time I really allow for happy accidents is in the composing stage where everything is digital and the undo button is then used liberally.

In this painting the apparent juxtaposition/contradiction is another example of the kinds of tension I employ in my work.

Do the droplets around the head signal impact, confusion, motion, or something more symbolic?

I paint bubbles quite frequently and they serve different functions depending on the situation. Here they are helping to convey the passage of time in what might be an otherwise airless or motionless world with no interaction of objects over any distance.

The surface feels hyper-controlled, almost airbrushed. What drew you to this high polish, nearly clinical finish for such a chaotic pose? Why did you choose a muted, restricted palette? How does the subdued colour scheme support the work’s emotional tone?

I used both airbrush and traditional brushes to paint “the Fool”.

When I make work it’s not my intention to draw attention to myself, I want the hand of the artist to be barely present, brush marks to be negligible. ‘Painterly’, as far as I’m concerned, is the state which paint naturally wants to default to without any help from me. I want to transform the materials into something else entirely and make the medium disappear. This is a very different approach from most contemporary artists, I think. In some respects, I relate more to the medieval model of the anonymous craftsman who is in service to something other than their individual ego and I don’t sign the front of works for this reason.

It’s a deliberately austere aesthetic which is designed to complement the somewhat-absurd proceedings taking place in the picture plane. As such the restrictive palette serves to focus the viewer’s attention on the sculptural form of the Fool. Colour, in this circumstance, would be a distraction.

There’s no ground or environment—just a figure floating against a gradient. Was that isolation important to the meaning of the piece?

Yes. The figures I paint live in a conceptual vacuum. I want them to exist as near as possible without any cultural or geographical signifiers. It shouldn’t matter where or when in the world the viewer is situated to “get it”.

The boot tread resembles contemporary streetwear/masculinity iconography. Was this a deliberate nod, and what does it contribute to the narrative?

A pictorial device as much as a compositional one. The tread was introduced to break up the picture plane surface and create a texture for light to interact with in a more interesting manner than a plain sole might otherwise have done. There is, however, a compass amongst the tread which always points north helping the Fool to orient themself.

The compass came from a childhood memory of Clark’s 1960’s Wayfinder shoes which I wore to school but the compass on the Fool’s sole is far more ornate than practical being, as it is, made of moulded plastic.

Do you see The Brilliant Fool as a commentary on modern identity—perhaps its instability, self-confidence, or the ways we collapse in private while performing competence in public?

As frustrating as it is to hear I really don’t think my interpretation of the painting is relevant. Apart from anything else painting is a nonverbal visual phenomenon and as such defies any literal interpretation even from me. The image is the message!

As we enter the second month of 2026, Naive John stands as a quietly emblematic figure: self-taught, stubbornly local, technically obsessive, resistant to trend. His hybrid method — pixels becoming pigment — feels perfectly attuned to now, without surrendering to it. “I love the production,” he said. “The subject is just an excuse for creation.” It’s a telling remark. For Naive John, painting isn’t commentary or spectacle. It’s the daily act of making something strange and precise — an act of belief.

For audiences encountering his work, his hope is simple and demanding. “I want people to feel something that can’t be described in words,” he says. “Something deep and transformative.” In a culture obsessed with explanation, that insistence feels quietly radical.

Liverpool has always made space for eccentrics and visionaries — those who work at their own tempo, outside the noise. In Naive John, it has one of its most singular: an artist whose laboratory hums on in Toxteth, where absurdity meets alchemy, and where the image, finally, is enough. A very special artist is indeed amongst us…

Follow @naivejohn on Instagram to follow his work.