Creative Spotlight: In Conversation with Paulina Kurzydlowska

Paulina Kurzydlowska – charting a practice where memory meets the modern

There is something quietly radical in the way Paulina Kurzydlowska works. She moves easily between memory, nature and the digital, letting thread, paint and pixel coexist in ways that feel both intuitive and deliberate. She describes herself as a mixed-media fine artist working across painting, textiles and digital processes, creating what she calls “new ways of experiencing our physical world.” Her work always seems to carry traces of landscapes remembered and landscapes reimagined, where natural forms brush up against pixelation, and where the analogue world doesn’t resist the digital but converses with it.

Paulina’s practice begins with a pull — an instinct to give shape to the emotional residue of the places she carries with her. She grew up between Poland and the Isle of Man before moving to Liverpool and now onto Manchester, and these shifting geographies seem to seep into her work. Her paintings often break into pixel-like patterns, as though digital interference is surfacing through layers of colour. Her photography lingers on moments in nature that feel almost like memories in real time. And her textiles — the hand-embroidered pieces that have become such a signature — hold their own duality: part image, part object, part memory.

When she speaks about her textile work, she says, “I like to describe my textile process as one in which I am painting with thread,” and the truth of that becomes clear the longer you look. The fronts of the works appear soft and subtle, but the backs reveal a hidden architecture — loops, connections, the quiet chaos of making — something like a visual echo of code or circuitry. That interplay builds a cyclical creative routine where each medium informs the next. Photography influences embroidery. Embroidery influences painting. Digital manipulation loops back and reshapes everything. For Paulina, this is a natural rhythm rather than a conscious strategy. As she puts it, “All these separate methods and materials intertwine depending on my desired outcome.”

Memory, place and nature keep calling her. She treats them not as static categories but as shifting, living territories. The forests of Poland, the coastline of the Isle of Man, the years in Liverpool — all of them settle into her creative intuition. She wants others to recognise something of themselves in these reflections. “I want to capture those memories through unique ways as an emerging artist,” she says, and that sense of purpose gives her work its gentle weight. It isn’t nostalgia; it’s something closer to translation, transforming personal experience into shared emotional space.

Her time at Liverpool Hope University becomes a pivotal part of that journey. She arrived ready to make work and found a network of tutors and peers who encouraged her to push further, work differently, risk more. One of the defining experiences of that period is her commission for Liverpool Cathedral: The Reimagining of the Nativity Tableau. It becomes both an artistic and practical undertaking. She thinks about materials, sustainability, structure, movement, and she makes the work her own. “I felt that I had enough creative freedom to make this incredible opportunity my own,” she reflects, noting how collaboration and communication keep the project fluid rather than overwhelming. The result is a piece that holds tradition and contemporary sensibility in balance, constructed from recycled materials and designed to live in a public, sacred space.

Technology remains a constant companion in her thinking. She doesn’t position digital work as the opposite of the handmade. Instead, she embraces the frictions and possibilities of both. She loves making visual reference to pixelation, sees potential in code-driven imagery, and finds ways to let the cold precision of digital processes soften into something tactile. “I believe my work conveys a unique perspective of how we can perceive these polarising mediums in the modern day,” she says, and it’s hard to argue otherwise. Her work sits exactly at the intersection where our contemporary lives unfold.

Being part of the Liverpool’s creative ecosystem gave her a sense of belonging.

She speaks warmly about fellow emerging artists — the energy, the generosity, the conversations that push her forward. But she’s also aware that opportunities rarely fall into place unprompted. She is proactive, reaching out, building networks, following leads, understanding early on that growth requires movement. That blend of community support and self-directed ambition shapes her career as much as her studio practice.

In that studio, she keeps a steady rhythm. She works every weekday, giving herself the continuity that complex, layered work requires. Once in the space, she allows herself to move fluidly — picking up embroidery while paint dries, revisiting digital drafts, stepping back from canvases to let intuition speak before returning with intention. It’s a balance that makes sense for an artist whose practice is built on interplay rather than hierarchy.

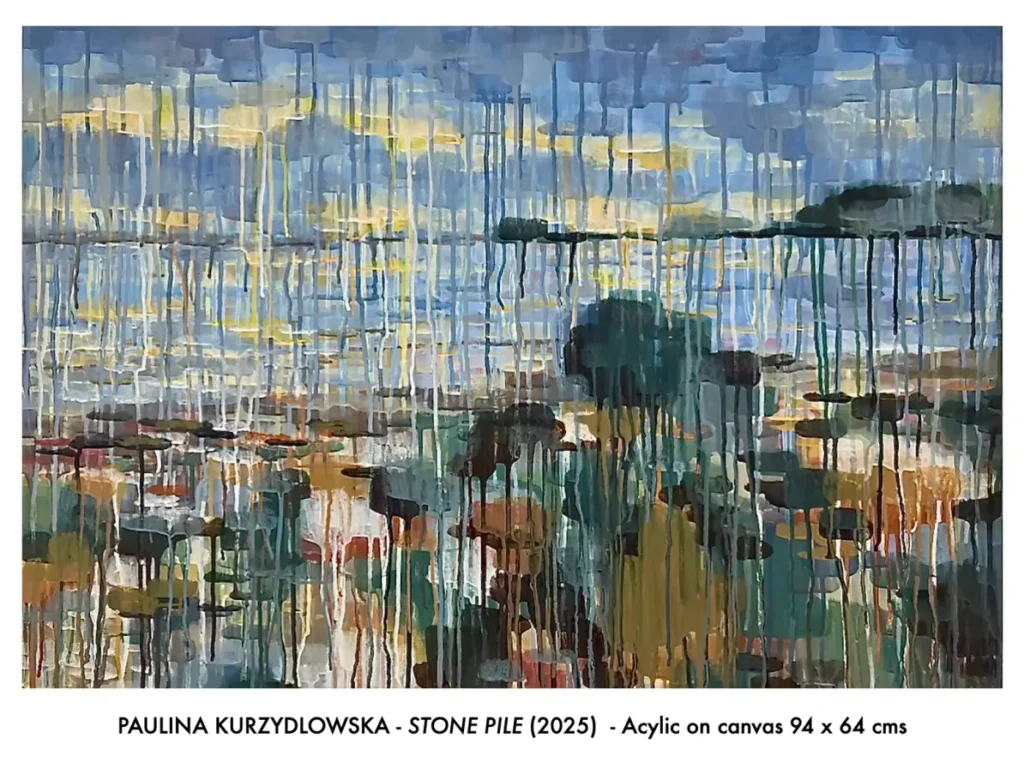

And at this junction, we should take the opportunity to discuss with Paulina a recent work – Stone Pile…

Let’s discuss Stone Pile — can you tell us what first inspired this piece? Was there a real place or moment behind it?

Stone Pile is based on a photograph I captured on Douglas Beach, Isle of Man one morning. I grew up on the Isle of Man, and the place holds great importance in my life. Douglas is a recognisable place especially through the depiction of the curve shoreline in the distance. Living by the sea is so serene and calming. The Albert Docks in Liverpool is another place which conveys a similar feeling of peacefulness to me.

There’s a real sense of movement in this paining — those vertical drips feel almost like rain or reflection. How did you develop that fluid, layered technique?

My watery layering technique arose from trying to be more ‘fluid’ with my brush strokes. The original aim was to experiment by being less controlling and to gradually build up opacity for a much more realistic depiction of my chosen reference image.However, I loved how these interesting textures were developing on the canvas as I added more paint. I was also pleased with how organically I built each stroke starting from the very first time the brush hit the canvas. I felt as though I had finally made something which I was impressed by and could call my own.

The palet moves between cool blues and earthy browns — what guided your choice of colours here?

The original reference image guided my choice of colours in Stone Pile. At this stage of my pracice, it is important for me to maintain this consistency to my colour references so that the locations, sites or landscapes I paint are recognisable to the viewer. I want to portray their authencity and idenity through colour while I manipulate their structure my brush.

The title Stone Pile is intriguing. What does it mean to you in relation to the image — is it literal, symbolic, or something in between?

For the tItle of this painting, I wanted to convey the symbolism of the sight I had been inspired by. Due to the fact someone else had constructed this pile of stones, I wanted to direct the viewer’s focus on this part of the composition. It is a trace of theirs that I happened to document one morning. Just like the author of the arrangement is unknown, the shape of the pile is undefined and up to interpretation within my painting. The title also carries a symbolic meaning as a navigational marker and a symbol of balance and hope for others.

Your work ocen explores memory and landscape. How much of Stone Pile is about what you see, and how much is about what you feel?

The compositional arrangement of Stone Pile is based on how the arrangement of stones I discovered one cloudy morning on Douglas Beach made me feel. There was a stillness in the air which is portrayed through the illusion that the drips on the canvas are frozen in time (like a photograph of its own) but also that they could melt down and morph into a new composition at any moment. This area of physical uncertainty in the painting parallels how I felt that day.

There’s a digital or pixel-like rhythm to the composition — those grid-like forms almost suggest a screen or coded pattern. Is that a deliberate nod to technology or digital space?

I deliberately nod to technology and a new presentation of digital spaces in a very analogue form within Stone Pile. Along with the other paintings in the same series, I allude to low- quality images, and I am very inspired by old retro depictions of video and digital display screens which are now ocen described as ‘bad quality’. I am interested in how these difficult-to-decipher images often grasp our attention more successfully than photographs that we are so used to taking on our phone screens. The act of deciphering Stone Pile therefore, poses a more difficult challenge for the viewer and encourages a more active participation in its viewing experience.

When you’re working on a painting like this, how do you know when it’s finished — when to stop layering, stop dripping, stop adjusting?

I rely on gut feeling. The period of actively working on my paintings is an instinctual one and this includes making decisions to clean my brush, to switch colours etc. The application of paint with my brush is quite fast and spontaneous. I would also describe moments such as these as very logical – I give myself time to think before I move on. The decision to stop adjusting the surface altogether is made once I step away from the work for a day or two. I make a final judgement as to its completi on based on that gut feeling. If further adjustments need to be made, I continue layering paint and step away once again. I repeat this process until the colours are the desired tone, and the vertical drips balance the pixel-like strokes to my liking.

What materials or tools were key to making Stone Pile — is it pure paint, or did you experiment with any mixed media?

Purely acrylic paint and water was used to create Stone Pile. The ratio of paint to water differs depending on the opacity of colour I am trying to achieve. Sometimes the work needs a very opaque pop of colour but other times it is a light wash which does the trick to blend the colours into the ones I need. I use two brushes: a hog-haired brush with a log handle to mix the paint in a plastic cup and a 50mm painter’s brush which is then used to soak up the mixture and apply it onto the canvas.

If someone were standing in front of Stone Pile for the first time, what would you hope they feel or take away from it?

I would hope they enjoy the playfulness of colours melting over the canvas and feel the warmth of sun peeking through the cloudy sky and reflecting upon the water below. If they stand extremely close, I hope they get lost in the picture plane, discovering little nuances every time they do so.

And finally, how does Stone Pile fit within your wider practice — is it a turning point, part of a series, or a step toward something new?

Stone Pile is comfortably situated as part of a series of 2025 paintings created through this repetitve process of layering paint over the canvas. I applied this watery painting technique for the first time in February of this year. Since then, I have maintained a consistent style and want to make more of these paintings in the future!

So as this year closes, her work continues to expand. She returns to Liverpool Cathedral on 7 December 2025 for the third installation of her Nativity Tableau, following the cathedral’s Son et Lumière event the evening before. In early December, she exhibits in Altogether Otherwise Manchester with the 1838 Collective’s Making & Mending exhibition, a theme that sits in perfect harmony with her textiles and her instinct to repair, reinterpret and rebuild. She also steps deeper into performance, joining the contemporary group An Image Is an Act Not a Thing after performing with Tiong Ang & Company at the Asia Triennial. A new performance is scheduled for early next year — another thread woven into her expanding practice.

Recognition continues to grow around her: awards, bursaries, exhibitions, the kind of early-career momentum that signals both promise and dedication. Yet what remains constant is her quiet attentiveness — the feeling that each stitch, each brushstroke, each pixel emerges from the same impulse to slow time down, to hold a memory long enough to understand it, and then to release it back into the world in a different form.

Paulina’s work carries that rare ability to hold tension without conflict. She doesn’t ask us to choose between past and present, digital and natural, memory and abstraction. She shows us that these things coexist — in her practice and in all of us.

As this year’s Creative Spotlight series draws to a close, it feels right to end with her: an artist who is not only shaped by the places she carries, but continually reshaping them into something new, textured and resonant. We wish her well on her artistic voyage.