Creative Spotlight: In Conversation with Sorrell Kerrison

Sorrell Kerrison — Threading Colour, Chaos and Compassion

In the vast and vibrant landscape of contemporary textile art, few voices hum with as much honesty, energy, and defiant colour as Sorrell Kerrison’s. A self-taught embroiderer, musician, and multidisciplinary artist now based in Liverpool, Kerrison’s practice is a deeply personal dialogue between sound, texture, and emotion — a visual symphony where needle and thread replace strings and frets. Once a touring musician and frontwoman, she has since translated that same punk energy and improvisational instinct into a new language of portraiture: hand embroidery that sings, snarls, and glows with raw human feeling.

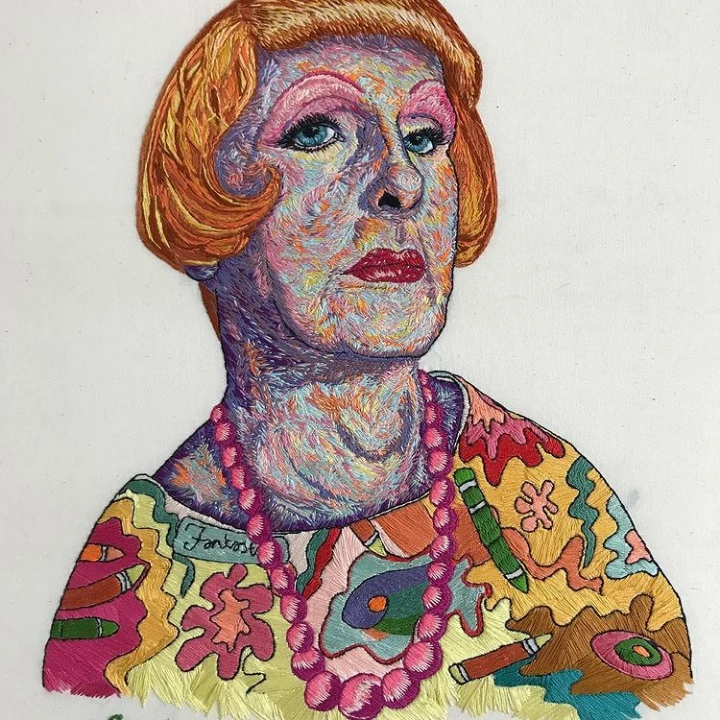

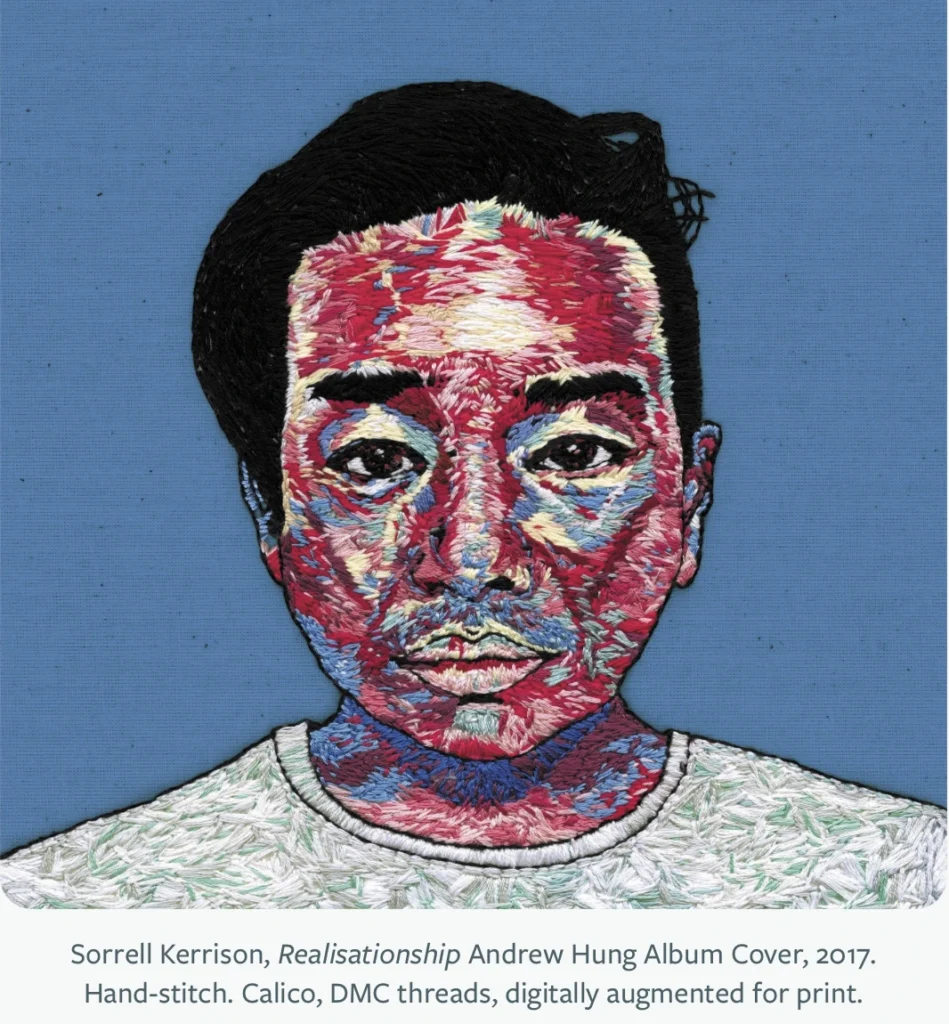

Her journey from the music scene to the art world was never a calculated career shift — more an organic evolution driven by curiosity, resourcefulness, and a need to create. What began as a practical act — sewing, printing, making band merch — grew into a love affair with textiles that offered both solace and stimulation. “I just like to take a skill and push it as far as I can take it,” she says, and that instinct for pushing boundaries defines her work today. Kerrison’s portraits of artists, musicians, and cultural figures — from Andrew Hung to Grayson Perry — vibrate with bold Fauvist colour and rhythmic stitchwork that borders on painting. They are, in essence, embroidered performances: slow, deliberate acts of creation that still pulse with the immediacy of live music.

Kerrison describes embroidery as “enforced patience” — a counterpoint to her “scribbled” drawings and kinetic energy — yet within that stillness lies immense vitality. Her work captures not just likeness but essence, the unseen frequencies that connect artist and subject. With synaesthesia shaping her perception of colour and texture, her palettes are intuitive, emotional, and deeply sensory. A Wednesday might be “a muted orange,” a person “a bright, clashing chord,” and it all finds its way into the stitched surface.

As Liverpool becomes the creative home she long sought — a city she praises for its openness, politics, and collective spirit — Kerrison’s art continues to expand. Whether working with her young son on tactile, playful installations or dreaming up immersive sound and animation projects, she remains committed to a practice that is inclusive, exploratory, and unapologetically heartfelt.

In this interview for Liverpool Noise’s Creative Spotlight 2025 series, Sorrell Kerrison reflects on the intersections of music, craft, and identity — and the power of patience, colour, and care to tell human stories one stitch at a time…

You made an “unconventional move” from the music industry into textile art. Can you describe the moment or experience that solidified your decision to make hand embroidery and visual art your primary focus, and how your time as a musician still informs your artistic discipline today?

I wouldn’t say I ever really transitioned knowingly, all the creative things I do take the lead at various times in my life. Making music and being in a band was everything for about 15 years and through that vehicle I learned other skills by accident really. For instance, you need merch making and you can’t afford to get them printed professionally, so you learn to make a screenprint yourself. Then you make totes and badges yourself. I learned to sew so that I could repair clothes or embellish them as I wanted. All these skills just developed over time. I loved embroidery and textile work as it was something I could easily travel with, pick up and put down on a whim. I don’t think I ever decided in a formal way that I was going to make embroidery my practice, I just like to take a skill and push it as far as I can take it. It just seemed like a natural development at the time.

You’ve called hand embroidery “enforced patience,” with some complex pieces taking hundreds of hours. How does the slow, meditative nature of stitching contrast with your preference for fast, ‘scribbled’ drawing and the energy of being a musician?

I am AuDHD and the ADHD part of my brain requires something to work on so that I can slow my brain down, the more I can keep my various sense occupied the calmer I feel and the Autism side requires a repeat stimming sensation. I am never really still. I enjoy movement and creating in all its forms. I don’t think I have ever been truly bored or ever ran out of ideas, so I am grateful to have these avenues out of which I can explore my interests. I also really love the sounds of crafting and making — the needle sliding in and out of canvas, knitting needles clacking together, the slop of glue, the sound of fabrics rubbing up against each other — I find it all really tickles my senses in a great way.

Does the ‘enforced patience’ allow for a deeper connection with your subjects?

I think the enforced patience comes from the fact that you cannot, no matter how much you try, go faster with embroidery… you learn to be a bit swifter with your motions, but the whole thing is just a very slow and considered craft. This definitely informs a stronger connection with the subjects. I also like to immerse myself in the work of my subject, reading about them, their own art or creations and trying to absorb as much about them as possible to get the ‘feel’ right on the canvas.

Your work is described using terms like “Fauvist-style,” “explodes with colour,” and “visually controlled chaos.” What draws you to this expressive use of colour and technique, and how do you decide on the vibrant colour palette for a new portrait, given the influence of your “punk feminist background” and improvisation?

I think the Fauvism literally comes from a very strong connection to works that use a similar colour palette and the bright and contrasting tones in my work. I have tried and failed many times to remain within a very limited colour palette or do something black and white. I try to allow myself the freedom to get into the flow of the piece and trust my instincts when it comes to colour choice. Everything you have done before influences your choices, I think my music background informs my decisions as much as what I had for breakfast that morning. It all pours into the same thing.

Your passion is making portraits of “creative people, and particularly the unsung heroes,” you admire. How do you select your subjects, and what are you looking to reveal or celebrate about them through your textile work?

As I am spending so much time with my subjects, dissecting them, absorbing their work and lives, I don’t choose anyone who I wouldn’t want to invite for dinner in real life. I have been asked whether I would do a certain President or a Leader and I’m like “No thanks, I wouldn’t want to break bread with them.” I chose people who have personally inspired me, would put interesting and beautiful things out into the world and hopefully, by way of my artistic homage to them through my portrait work, I am also adding to the beauty in the world.

What drew you to Grayson Perry, and specifically his alter-ego Claire, as the subject of this embroidered portrait?

I’ve been a fan of Perry’s work for a long while. Not only because their creative practice includes mediums that I love and use in my own practice, such as textiles and ceramics, but also because of their philosophy and approach to life. I love that Grayson is playful in his own personal decor, which includes messing with gender expectations and humour.

Did you approach this piece differently knowing that Grayson Perry himself is a textile enthusiast and potter, someone who also blurs the boundaries between art and craft?

I don’t think I approached this particular portrait differently. By this one I felt like I had in fact got in my stride of my own style to my embroidery portraits and this felt like a very comfortable subject for this.

The work radiates with Fauvist colour. How did you decide on your palette when interpreting skin tones, textures, and costume?

I’m AuDHD and I’m synesthetic. I basically feel texture and colour connected to the everyday mundane. For instance, a Wednesday is a medium muted orange colour, but a Thursday is more pastel green. I do this with people too — their personalities and elements give me a sense of colour and texture. With the reference for Claire I built on the colours in the real photograph but also added colours that I felt from their character and everything I’ve gleaned from their art and reading their literature.

Your stitches almost mimic the energy of brushstrokes — do you see your embroidery practice as closer to painting than to traditional textile work?

When I draw, I tend to use biro and simple pens. I draw quickly and ferociously. You are right that the same kind of strokes and movement ends up in the final embroidered pieces. The pre-sketches inform the direction of the stitches and I try to keep that flow and energy in it.

Claire’s patterned dress is a riot of colour and form. Was that section more liberating or more challenging to render in embroidery?

I used a more 2D flatter rendering of the dress than I did the face. I like using this as a juxtaposition between the character and personality in the face against a flatter clothing structure.

What role does texture play in capturing the individuality and energy of your sitters, particularly someone as flamboyant as Claire?

The direction, movements and flow of the ‘feeling’ is what I tend to use to inform the texture rather than the direct mimicking of what I see in front of me.

Embroidery has historically been coded as “feminine craft.” Do you see this portrait as an intentional dialogue with themes of gender and performance?

I’ve been fascinated to see the crafts that fall under ‘women’s work’ get a bit of a promotion in the art world over the last five years. Grayson is a man, using the guise of a woman and delving into mediums which are considered feminine and he is lauded with praise for it. If a woman is a cook, a man is a chef… I often find this polarised expression jarring and I don’t know how Grayson approaches it politically, but I know, in and of myself that women and ‘women’s work’ is historically never taken as seriously as a man’s work, even when enacting that which is coded female.

How long did this piece take to complete, and which stage of the process felt most absorbing or rewarding for you?

I think this piece took around three months and maybe circa 300+ hours. I always do the eyes first — the windows to the soul and all that. Once I get those down I can relax into the piece and get more into my flow state, before that I am picky and working on getting the composition right. By the time I get to the clothes I’ve lost all handle on space and time and I’m properly in flow state.

Do you view Grayson Perry as Claire as a homage to Perry, or more as a conversation between two artists working at the edge of art and craft?

As I mentioned before, I think it is a political comment on the part of Perry to split his visual character into two distinct masculine and feminine coded costumes. I love that he speaks to the duality existing in one body and in all bodies. Costume as protest, costume as humour. It’s all involved and entangled. It’s both serious and utterly stupid at the same time — which I love. Different people will take different things from his alter-ego being present. Some as merely a novelty and some as a very pointed statement on societal expectations. It’s both and neither at the same time…

You have mentioned that many embroidery artists avoid the face because it’s the “hardest part to get right,” but you “faced it head on.” What challenges and rewards have you found in focusing on the human face as your main subject matter?

The human face is difficult for many reasons, especially famous faces. As they are known, people can be judgemental if they look ‘wrong’. If I had just done a random person then people would maybe be impressed with the skill of the work, but when I am doing a person who they can reference a lot of other things fall into place. Whether it is true to life, or an expression of what I feel they are. I hope to straddle the line between these things and find a ground between the knowing of the face and discovering new things about them through my depiction.

You’ve completed significant commissions, including the album cover for Andrew Hung’s Realisationship and four portraits for the permanent collection at Bolton Museum. How does your approach differ when creating a piece for a commercial release versus a historical museum’s permanent archive?

It really doesn’t differ too much to be honest. At its core it’s all about gathering research materials, figuring out what the client wants and what I am able and comfortable in delivering. With an album you can listen to the music, work with the music and figure it out from there. With the museum it was more about archival photos and materials from the individuals I was depicting. It’s all about making sure that the research and pre-sketches are done so when that needle hits the canvas for the first time it’s ready to go.

As the winner of the 2020 Hand & Lock Open Art category, you now mentor potential winners. What is the most important piece of advice you offer emerging textile artists, especially those making a similar career transition or grappling with the perception of textiles as ‘craft’ versus ‘art’?

A lot of those who enter that prize are already in higher education for embroidery-specific works and have a pretty solid idea of what they want to do in their career. My mentoring ends up being mostly to do with how to present their moodboards and their final piece so that the judges have the best sense of their work and what they are trying to achieve. As a winner of that prize I was quite an outlier. I have had zero formal embroidery or textiles training, my methods of pattern transference and sewing are all very haphazard and self-taught. Most, if not all of the people who enter that prize are already on their way to being ‘professionals’ in the field. I think I can offer a perspective and methods outside those that are formally taught and hopefully help working-class people see that prizes and formal art paths are not the only way forwards.

Your exhibition title Chwarae Teg / Fair Play (Welsh for ‘Fair Play’) focused on nostalgia, playfulness, and reconnecting with a sense of wonder. How did your exploration of childhood innocence and play translate into the tactile experience of your work, and how do you incorporate interactive or participatory elements into your exhibitions?

I co-made this piece with my son (who was then 4–5 years old), and he is non-verbal and Autistic with severe assistance needs. I wanted to involve my son in my work and practice partly as I saw that he was getting a lot from being able to express himself visually when he struggles and is mostly unable to verbally, and also for the development of my own practice.

As we know, I can be a bit chaotic, but also within that a sense of perfectionism. I wanted to garner some of that childlike ability to create art and not worry about whether a critic was going to ‘get it’ and just let it be what it was. We made a den out of quilts that I had made partly for this exhibition and partly for one in lockdown for the Biennial 2020 which never got shown. We made an animation depicting a child in the womb and connectivity to all the energy in the world. I even made a quilt for the wall that was unfinished and unstretched, allowing the mistakes and holes to be part of the work. Seeing his joy in the creation and his instinct when it came to choosing colours and materials helped me to let go a little. We actually have our first art residency in January 2026 in Mawddach, West Wales. I hope to keep developing our work in tandem as it helps my practice and it also assists in his personal expression.

You’ve moved from North Wales to London, Bristol, and now reside in Liverpool. How has the environment and creative culture of Liverpool influenced your current multidisciplinary practice and outlook as an artist?

Growing up in a pretty but isolated valley in Wales where I was relentlessly bullied for my music tastes and creative ambition, I have always been on the move to try and find a place where I can create and feel comfortable with the people around me. I have found that in various places over the years but I adore Liverpool. It’s got the most supportive and truly open people living here. All things are possible. I don’t feel like anything is being gatekept and people really want to encourage and assist you in producing work in whatever shape and form that takes. It’s a really special place and somewhere I feel I have been able to thrive creatively. I also love that the politics is majorly on the socialist side and that there are so many passionate people making sharing and caring for our communities part of the everyday. I really love being in Liverpool. It has my heart!

You have stated that you are “committed to continual growth and exploration.” What current projects or areas of your multidisciplinary practice — in sound (Pluvial), film, or ceramics — are you most excited to develop next, and how do they feed back into your textile work?

I’m always working on about eight different things! At the moment I am working on a commission to make lanterns and lighting sculptures for a parade. I have decided to make an effort to record some new musical material, which will also include animated videos in accompaniment. I’m hoping that the residency time at the beginning of January will kick off the year in my research and gathering what I need to figure out what this project is going to materialise. I have this dream to make an immersive album. Music, animation, art gallery showing — the project is all things at once. So, to make this a reality I have to focus on what is coming next and how to hone this down so it isn’t just a dream and becomes a tangible thing!

For more information about Sorrell Kerrison visit sorrellkerrison.com.